Leen Helmink Antique Maps

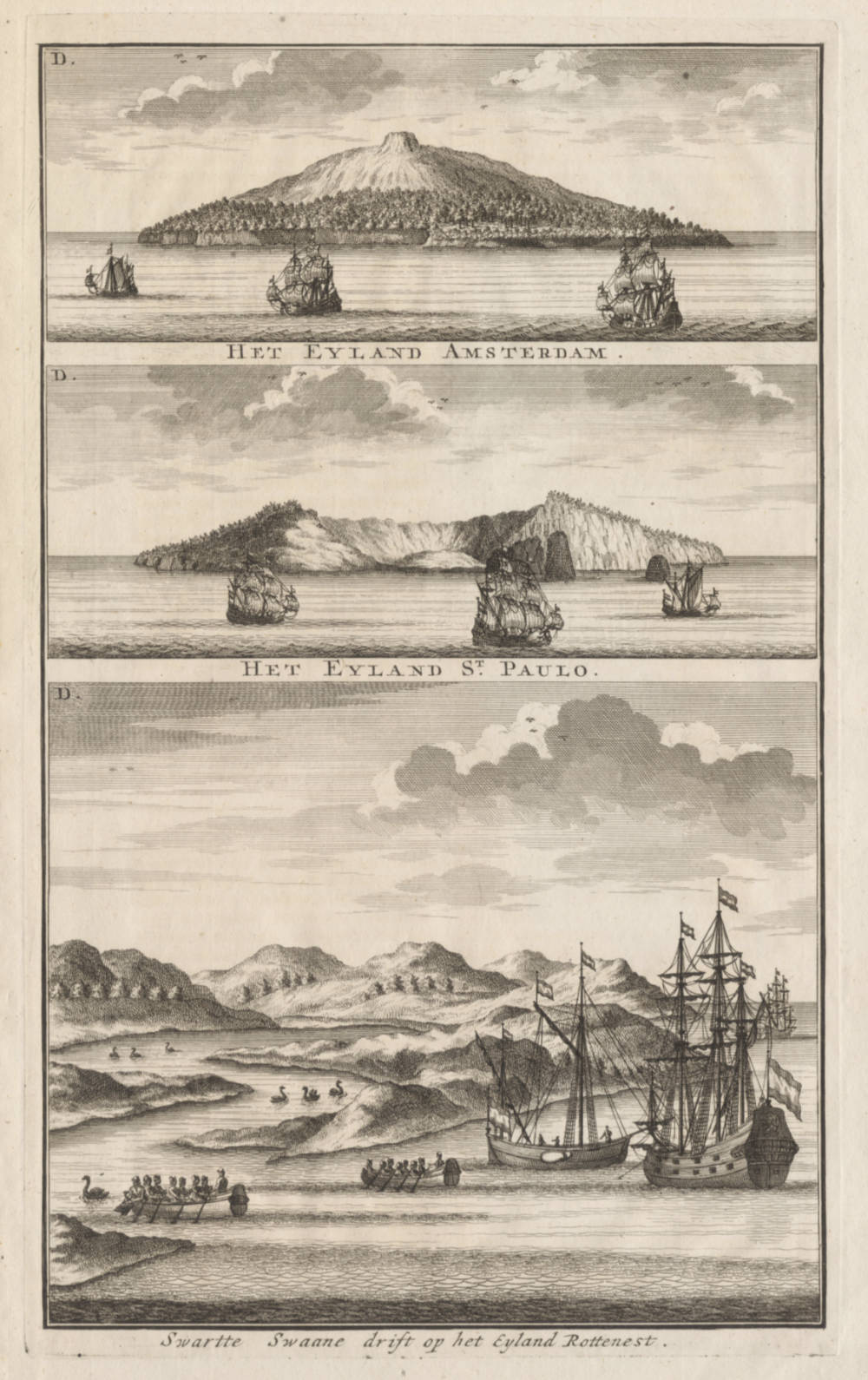

Old panorama view of the Swan River in Western Australia, by François Valentijn

Stock number: 18953

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

François Valentijn (biography)

Title

Swartte Swaane drift op het Eyland Rottenest

First Published

Amsterdam, 1726

This Edition

1726

Size

28.7 x 17.3 cms

Technique

Condition

mint

Price

$ 1,750.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

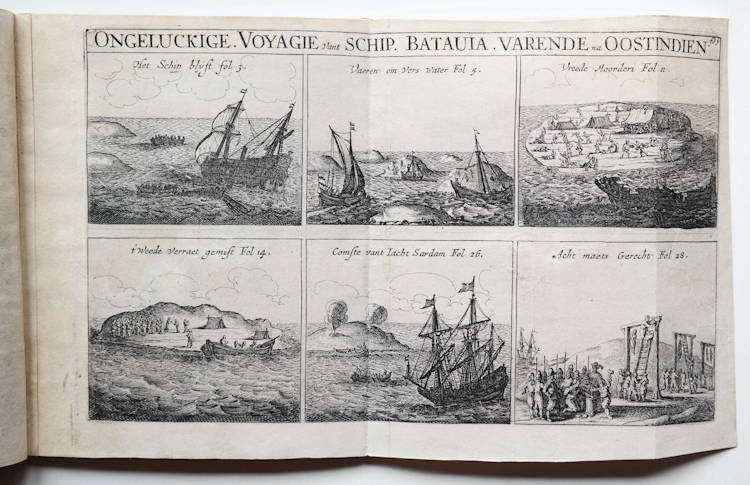

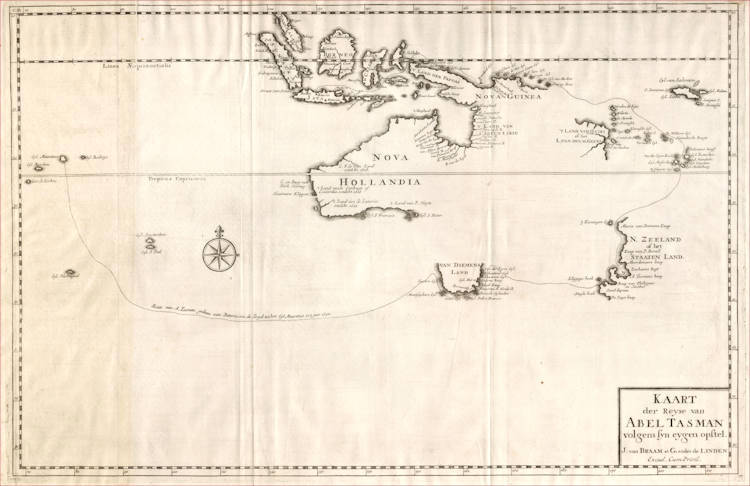

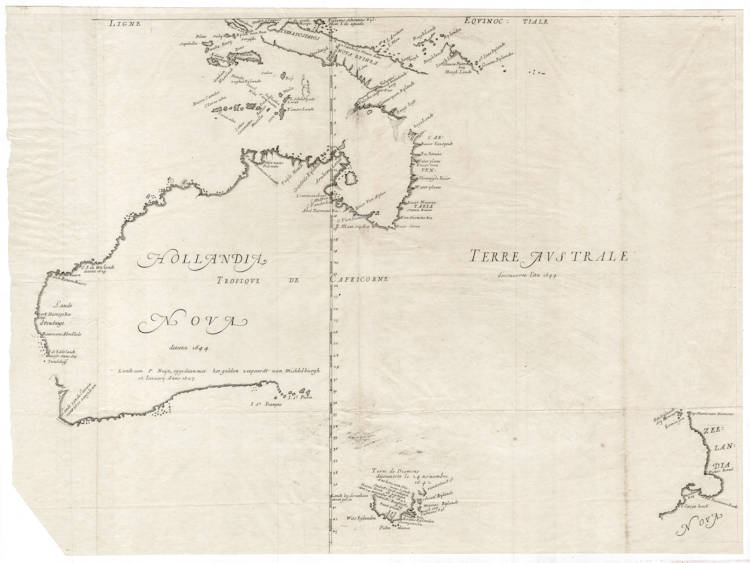

The first printed view of Australia. On one copperplate with two other views of the islands Amsterdam and St Paul, two tiny volcanic islands in the southern Indian Ocean. De Vlaming was the first to succeed to land on these islands, which were considered very high risk for navigation and for landing.

Black swans at the entrance to the Swan River with Willem de Vlamingh's vessels ’t Weseltje, Geelvinck and Nijptangh at anchor. From François Valentijn, Oud-en Nieuw Oost-Indien, 1726.

This is the original copperplate in first state. The plate would later be re-used by Johannes II van Keulen for his "Secret Atlas of the VOC". A copy of this plate would be re-issued by Jacob van Schley in ca 1758 (example online here) and by Alexander Dalrymple in 1780 for the London Hydrographical Office, although he conveniently leaves out de Vlamingh's fleet and sloops.

Condition

No restorations or imperfections. Pristine collector's condition.

On 29 December 1696, he landed on Rottnest Island. He saw a giant jarrah, numerous quokkas (a native marsupial), and thinking they were large rats he named the island "rats' nest" (Rattennest in Dutch) because of them. He afterwards wrote of it in his journal: "I had great pleasure in admiring this island, which is very attractive, and where it seems to me that nature has denied nothing to make it pleasurable beyond all islands I have ever seen, being very well provided for man's well-being, with timber, stone, and lime for building him houses, only lacking ploughmen to fill these fine plains. There is plentiful salt, and the coast is full of fish. Birds make themselves heard with pleasant song in these scented groves. So I believe that of the many people who seek to make themselves happy, there are many who would scorn the fortunes of our country for the choice of this one here, which would seem a paradise on earth".

On 10 January 1697, de Vlamingh ventured up the Swan River, the first Europeans to do so. They are also the first Europeans to see black swans, and De Vlamingh named the Swan River (Zwaanenrivier in Dutch) after the large number they observed there. They brought a couple of black swans to Batavia, but unfortunately those did not survive the voyage. The Dutch party found aboriginal villages and huts, hastily abandoned, and the natives themselves were not to be found. The crew split into three parties, hoping make contact or to bring one to Batavia, but about five days later they gave up.

Willem de Vlamingh's expedition to explore Western Australia was well-prepared and is well documented. Artist Victor Victorszoon was included in the fleet and made watercolors, that were rediscovered in the Maritime Museum of Rotterdam by professor Gunter Schilder in the 1970s. The whole expedition is extensively analysed in Gunter Schilder, De ontdekkingsreis van Willem Hesselszoon de Vlamingh in de jaren 1696-1697. Den Haag: Nijhoff, 1976.

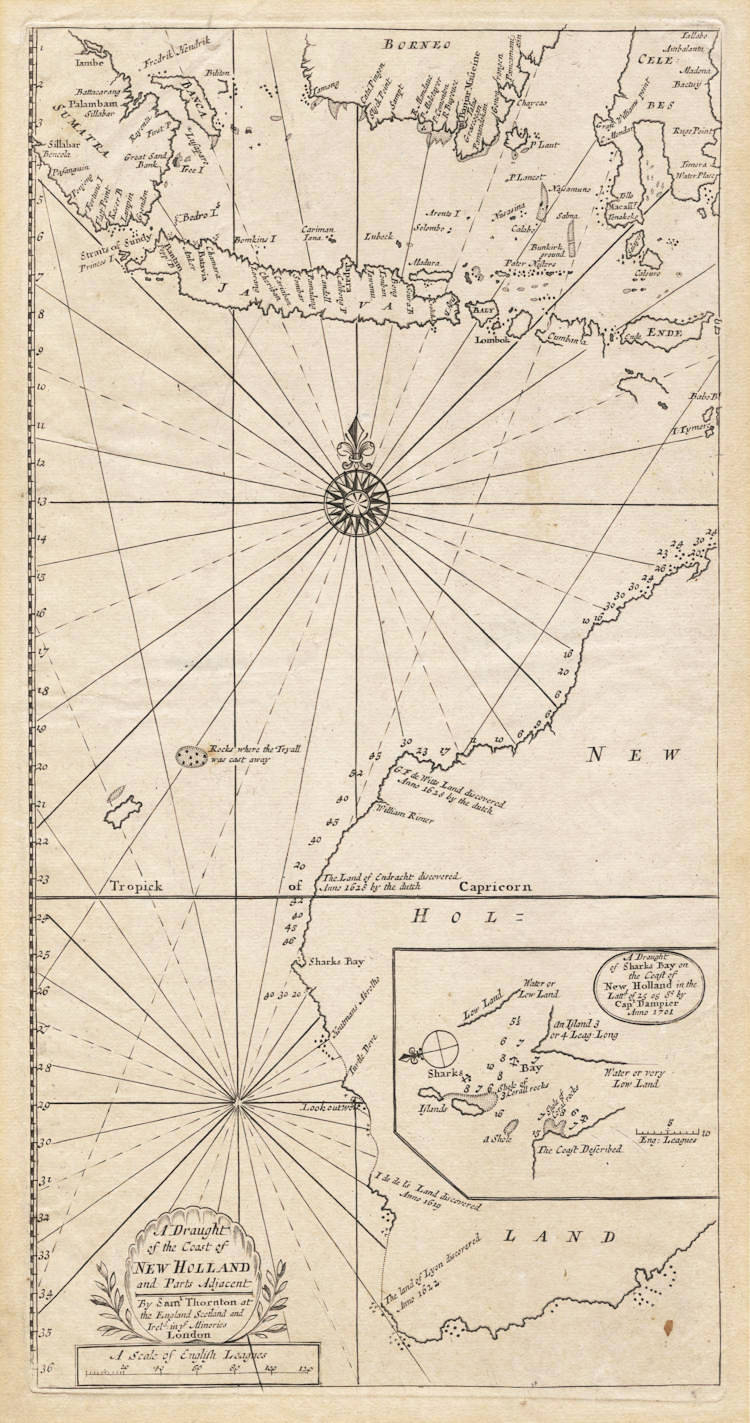

On 22 January, they sailed through the Geelvink Channel. The next days they saw ten naked, black people. On 24 January they passed Red Bluff. Near Wittecarra they went looking for fresh water. On 4 February 1697, he landed at Dirk Hartog Island, Western Australia, and replaced the pewter plate left by Dirk Hartog in 1616 with a new one that bore a record of both of the Dutch sea-captains' visits. The original plate is preserved in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

The daily journal of Batavia Castle upon the safe arrival of this fleet is transcribed and translated online here: Brief Account of the Principal Events on the Voyage of the Frigate De Geelvink to the Southland, 20 March 1697.

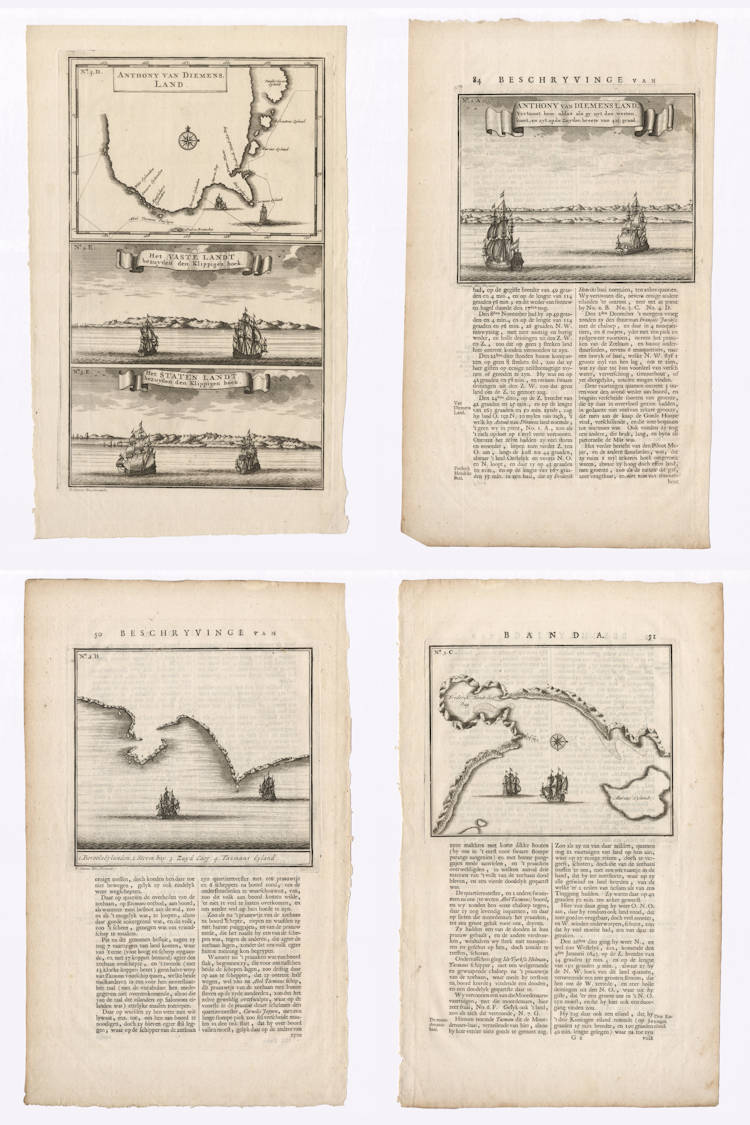

"After the expeditions of Abel Tasman (1642 & 1644) there was little Dutch activity relating to the South Land. This lasted until 1694 when the East Indiaman Ridderschap van Holland was lost. It was assumed to have been shipwrecked in the Southland since some maintained that this country lay further to the west than indicated by the charts. Again the VOC had a reason to explore and survey the dangerous coasts of Australia.

Willem de Vlamingh, an experienced VOC officer, was appointed to search for signs of the wrecks and possible survivors from the Ridderschap van Holland and the Vergulde Draeck, which was lost in 1656. They were also to find new staging places between the Netherlands and the Cape of Good Hope, and from the Cape to Java. For this reason de Vlamingh’s route included the islands of Tristan da Cunha, Amsterdam and St Paul.

For this expedition the VOC directors decided to build a new fleet, the hooker Nijptangh, the galliot ‘t Weseltje and the frigate Geelvinck. With its shallow draft ‘t Weseltje would prove very useful for exploring close to the coast.

On 29 December 1696 seaman Caspar Broel on board the Geelvinck, first sighted ‘the Fog Island dead ahead’, present-day Rottnest Island. Exploration of the Island, Swan River and the coast to the north followed. At Shark Bay, de Vlamingh recovered Hartog’s plate and left one of his own for posterity.

‘…various people keep saying that the said land would be more westerly than the charts show…’

‘…the coast in that region is not yet well known, and is not very clean…’

On Rottnest Island ‘found there the finest wood in the world, from which the whole land was filled with a fine pleasant smell’.

‘God in heaven be thanked for our safe voyage’. Willem de Vlamingh in Günter Schilder, Voyage to the Great South Land …(1985).

(Western Australia Museum)

‘About one o’clock in the afternoon, we anchored in the roadstead of Batavia, with five fathoms depth God be praised for a safe journey’. These lines were written by Captain Willem de Vlamingh on March 20 1697 at the end of the log which he had kept during his expedition to the Southland (Australia). On the same day, a clerk in Batavia reported De Vlamingh’s arrival, as we can read in the daily journals of Batavia Castle.

This marked the final act of an expedition of three ships which had sailed eleven months earlier, in May 1696. After long deliberations, the VOC directors in the Netherlands had decided to organize this expedition. Three goals were set In the first place, the ships had to look for a VOC ship, De Ridderschap van Holland, which had departed from Flushing in 1693. She had reached Cape Town and had continued her voyage to Batavia from there, but since then nothing had been heard of her. Although this had all happened three years before, not all hope had been abandoned of finding De Ridderschap van Holland and her crew. Maybe she had been stranded somewhere in the Indian Ocean on the shores of the islands of Amsterdam or St Paul, or on the west coast of Australia. Nevertheless, before investigating these places, De Vlamingh was ordered to sail to the Tristan da Cunha group in the South Atlantic.

All these islands and coasts had to be surveyed, described and meticulously mapped. A report was expected which would outline the commercial opportunities for the Company. Over and above this, the expedition had a scientific aspect. At the request of the Amsterdam VOC director, the scholar Nicolaas Witsen, De Vlamingh and his men were to try to capture one or more inhabitants of Australia and transport them to Batavia or even to the Netherlands. They might possibly provide useful information about the land and its culture. Witsen also urged that an artist be attached to the crew. After well-organized preparations, De Vlamingh commenced his voyage on the frigate Geelvinck accompanied by two smaller ships, the Nijptang en Het Wezeltje. A 198 man crew embarked on the ships, including the painter Victor Victorszoon.

The expedition began successfully. Tristan da Cunha was reached and explored. From there the ships sailed for Cape Town, where three Asian persons were taken on board. De Vlamingh expected them to serve as translators in Australia. The islands of Amsterdam and St Paul were surveyed and after that, for almost two months, the west coast of Australia was investigated and mapped However, although they came upon some wreckage of Dutch ships, they found no trace of De Ridderschap van Holland or her crew. From Australia the ships sailed to Batavia. The goal of the expedition had been achieved, but only just The lost ship was not found and, although De Vlamingh could give full reports of the geographical and physical aspects of the plac-es he had inspected, as well as the flora, fauna and inhabitants, the directors were disappoint-ed that he had not investigated larger areas of the Southland. De Vlamingh’s conclusion was that Australia would not in any way be useful to the Company In this wild, dry and desolate land no minerals were to be found and commercial relations with the inhabitants carried absolutely no prospect of any profit. After reporting extensively, De Vlamingh returned to the Netherlands. His voyage was the last VOC expedition of any importance to Australasia.

(van Gelder)

François Valentijn (1666 – 1727)

François Valentijn (17 April 1666 – 1727) was a Dutch minister, naturalist and author whose Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën ("Old and New East-Indies") describes the history of the Dutch East India Company and the countries of the Far East.

François Valentijn was born in 1666 in Dordrecht, as the eldest of seven children of Abraham Valentijn and Maria Rijsbergen. He lived most of his life in Dordrecht; however, he is known for his activities in the tropics, notably in Ambon, in the Maluku Archipelago. Valentijn studied theology and philosophy at the University of Leiden and the University of Utrecht before leaving for a career as a preacher in the Indies.

In total, Valentijn lived in the East Indies for 16 years. Valentijn was first employed by the VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) at the age of 19 as minister to the East Indies, where he became a friend of the German naturalist Georg Eberhard Rumpf (Rumphius). He returned and lived in the Netherlands for about ten years before returning to the Indies in 1705 where he was to serve as army chaplain on an expedition in eastern Java.

He finally returned to Dordrecht where he found time to write his Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (1724–26) a massive work of five parts published in eight volumes and containing over one thousand engraved illustrations and some of the most accurate maps of the Indies of the time. He died in The Hague, Netherlands, in 1727.

Valentijn probably had access to the VOC's archive of maps and geographic trade secrets, which they had always guarded jealously. Johannes van Keulen II (d. 1755) became Hydrographer to the V.O.C. at the time Valentijn's Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën was published. It was in the younger van Keulen's time that many of the VOC charts were first published, one signal of the decline of Dutch dominance in the spice trade. One uncommon grace afforded Valentijn was that he lived to see his work published; the VOC (Dutch East India Company) strictly enforced a policy prohibiting former employees from publishing anything about the region or their colonial administration.

(Wikipedia)

"The first book to give a comprehensive account, in text and illustration, of the peoples, places and natural history of Indonesia."

(Bastin & Brommer)

The Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien was created both from the voluminous journals Valentijn had amassed during his two stays in Southeast Asia, as well as from his own research, correspondence, and from previously unpublished material secured from VOC officials. The work contained an unprecedented selection of large-scale maps and views of the Indies, many of which were superior to previously available maps.

(Suarez)

François Valentijn's Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien (Old and New East Indies) has for long been regarded as a primary source of information on a number of regions of maritime Asia. It is a veritable encyclopaedia, bringing together an array of facts, trivial and vital, from a wide range of contemporary and earlier literature, acknowledged and unacknowledged, and contains valuable excerpts from contemporary documents of the Dutch East India Company and from private papers.

(Arasaratnam)

François Valentijn was born on April 17, 1666, in the city of Dordrecht, the Netherlands, as the eldest of seven children of Abraham Valentijn and Maria Rijsbergen. He studied theology at the universities of Utrecht and Leiden. During his life he spent nearly fifteen years as a minister in the Dutch East-Indies (1685–1694 and 1706–1713), mostly in the Moluccan Archipelago. In 1692 he entered into matrimony with Cornelia Snaats (1660–1717) who bore him two daughters. Valentijn died on August 6, 1727, in the city of The Hague. Valentijn is often noted for his role in discussions about early translations of the Bible into Malay. However, his established reputation rests on his multivolume work on Asia titled Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indië (Old and New East-Indies).

REVEREND VALENTIJN IN THE MOLUCCAS

At the age of nineteen, Valentijn was called to the ministry on Ambon Island, the chief trade and administrative hub of the Moluccan Archipelago. In the city of Ambon, he preached in the Malay language and trained local Ambonese assistant ministers, while also having to inspect some fifty Christian parishes in the region.

In the 1600s the catechism and liturgy were offered in so-called High-Malay, which most local Christians did not understand. Valentijn fervently opposed the use of High-Malay and instead propagated Ambon-Malay because, in his opinion, all Christian communities in the Indies understood this local dialect.

During his stay in Ambon, a number of Valentijn's colleagues blamed him for paying too much attention to his wife and making a living from usury. On top of these accusations, he was found guilty of manipulating official church records. The relationship with his colleagues grew tense because Valentijn disliked his task of inspecting the Christian parishes on other islands. In 1694 he returned to the Netherlands where he spent much time on his Bible translation.

In 1705 Valentijn returned to Ambon. During this period, Reverend Valentijn got into a conflict with the governor of Ambon about too much interference of the secular administration in church affairs without the consent of the church administration. This conflict worsened after Valentijn rejected his call by the central colonial administration to the island of Ternate. In 1713 his repeated request for repatriation was finally met.

THE MALAY BIBLE TRANSLATION

In 1693 during a meeting with the Church Council of Batavia, Valentijn announced that he had completed the translation of the Bible into Ambon-Malay. The Church Council refused to publish Valentijn's translation because two years earlier they assigned the task of translating the Bible into High-Malay to the Batavia-based Reverend Melchior Leydecker.

After Valentijn returned to the Netherlands in 1695, he rallied support for his translation. A heated discussion unfolded, in which Valentijn and, amongst others, the Dutch Reformed synods of both the provinces of North- and South-Holland, opposed the critique of Leydecker and the Church Council of Batavia. The Council's criticism largely concerned Valentijn's use of a poor dialect of Malay. The synods in the Netherlands were not in the position to participate in the debate as most relevant linguists resided in the Indies, but Valentijn's personal network most likely contributed to the support for Valentijn's translation.

In 1706 a special commission of ministers in the Indies inspected a revised edition of Valentijn's translation but still noticed a number of shortcomings. Although Valentijn told the commission that he would redo the translation, the final revised edition was never presented to the Church Council. The Council eventually decided to publish Leydecker's High-Malay translation, which was used in the Moluccas from 1733 onward into the twentieth century.

OUD EN NIEUW OOST-INDIË

From 1719 onward, Valentijn, as a private citizen, devoted himself chiefly to his magnum opus, Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indië (ONOI), comprising his own notes, observations, sections of writings from his personal library, and materials trusted to him by former colonial officials. In 1724, the first two volumes were published in the cities of Dordrecht and Amsterdam, followed by the following three volumes in 1726. This work comprises geographical and ethnological descriptions of the Moluccas and the trading contacts of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) throughout Asia.

Scholars consider this substantial work the first Dutch encyclopedic reference for Asia. ONOI contains factual data, descriptions of persons and towns, anecdotes, ethnological engravings, maps, sketches of coastlines, and city plans, as well as excerpts of official documents of the church council and colonial administration.

Valentijn wrote in an uncorrupted form of Dutch, which many contemporary writers were not able to compete with. The structure of Valentijn's colossal work is rather chaotic: the descriptions of more than thirty regions are erratically spread over a total number of forty-nine books in five volumes, each consisting of two parts, and held together in eight bindings.

Since the publication of ONOI, numerous scholars have accused Valentijn of plagiarism. It is true that he included abstracts of other works, such as the celebrated account on the Ambon islands by Rumphius, without referencing them properly. However, general acknowledgment of sources can be found in several places, for example, in his preface to the third volume.

THE INFLUENCE OF VALENTIJN'S WORK

For almost two centuries, Valentijn's work was the single credible reference for Asia. ONOI was therefore used as the main manual for Dutch civil servants and colonial administrators who were sent to work in the East Indies.

Valentijn's work is still a major source for historical studies on the Dutch East Indies. For example, the reference book on Dutch-Asiatic shipping in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (The Hague, 1979–1987) was compiled on the basis of materials derived from Valentijn's work. The importance of ONOI for the historical reconstruction of other regions is clearly demonstrated by the publication of English translations of Valentijn's parts concerning the Cape of Good Hope (1971–1973) and the first twelve chapters of his description of Ceylon (1978).

Valentijn's work also proved to be of great importance for the natural history of the Moluccas. Valentijn included in ONOI descriptions by Rumphius on, for example, Ambonese animals, while Rumphius's original unpublished manuscript was later lost. In 1754 Valentijn's part on sea flora and fauna was separately published in Amsterdam, and some twenty years later translated into German. It was only in 2004 that the complete ONOI was reprinted and made available to a larger public.

(Encyclopedia.com)

Related Categories

Related Items