Leen Helmink Antique Maps

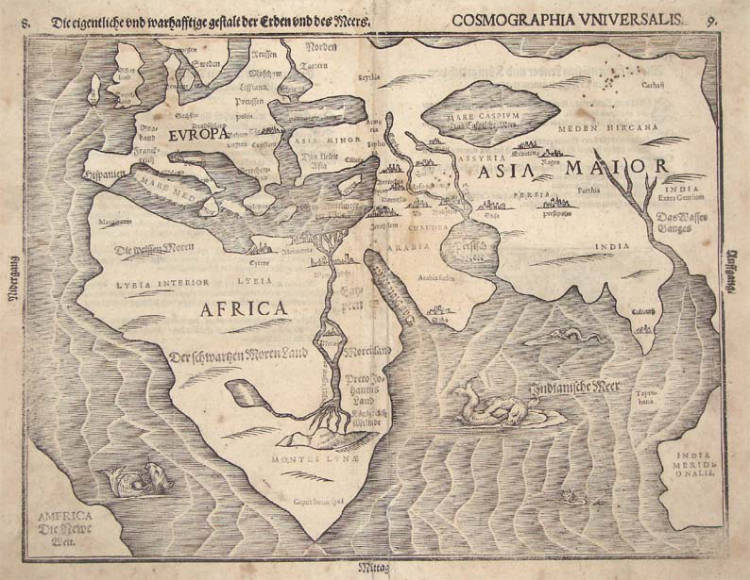

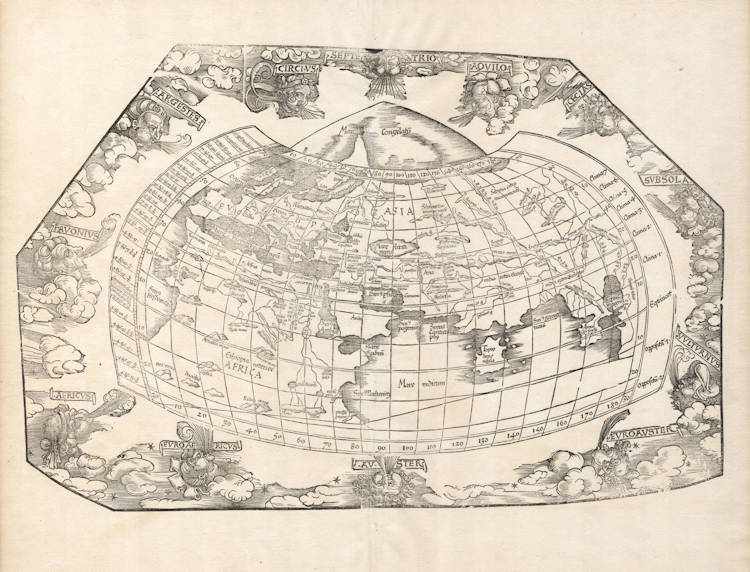

Antique map of the World by Münster / Grynaeus / Holbein

Title

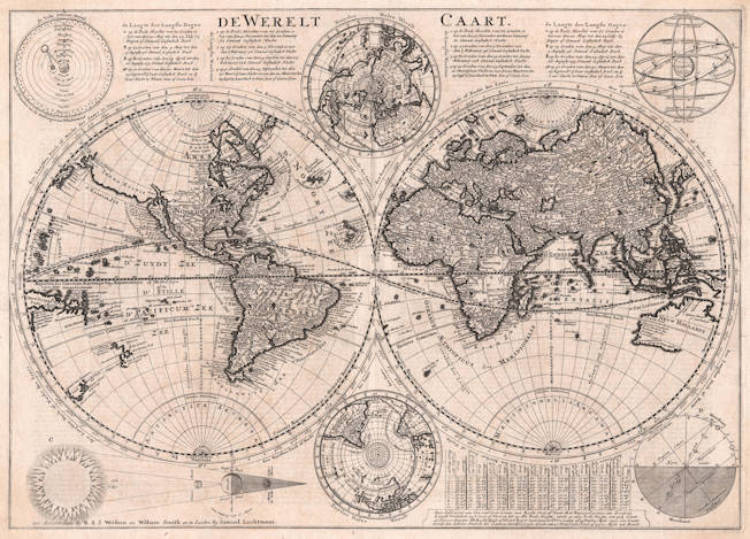

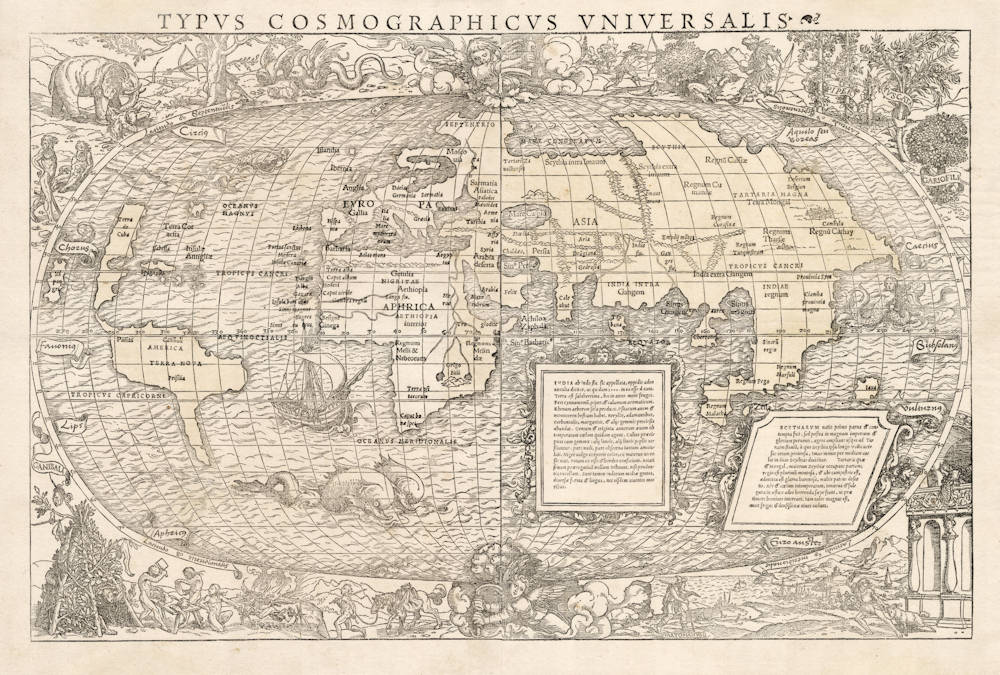

TYPUS COSMOGRAPHICUS UNIVERSALUS

First Published

Basle, 1532

This Edition

1532 first edition

Size

35.5 x 55.5 cms

Technique

Condition

mint

Price

$ 45,000.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

A stunning example of one of the most spectacular and sought-after early maps of the world.

The woodcut map of the world is a supreme example of the collaboration of the famous cartographer Sebastian Munster and his friend Hans Holbein the Younger, who was responsible for the artistic decorations inside and outside the map. They both worked in the German-Swiss city of Basle at the time.

The depiction is famous for showing two angels that use cranks at the poles to rotate the earth around it's own axis, in line with Nicolaus Copernicus heliocentric model that would not be published until 1543, more than ten years after the publication of this map. In fact, Copernicus' heliocentrism (Earth rotating daily and revolving around the Sun, as opposed to the Ptolemaic geocentric model with the earth in the center of the universe and the Sun, Moon, planets and stars all orbit earth), was not popularized until it was championed by Galileo Galilei in the early 17th century.

Galilei was met with opposition from within the Catholic Church and from some astronomers. The matter was investigated by the Roman Inquisition in 1615, which concluded that heliocentrism was foolish, absurd, and heretical since it contradicted Holy Scripture.

Galileo later defended his views in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), which appeared to attack Pope Urban VIII and thus alienated both the Pope and the Jesuits, who had both supported Galileo up until this point. He was tried by the Inquisition, found "vehemently suspect of heresy", and forced to recant. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

Condition

The unobtainable first edition first state, lacking in all collections. Printed on two sheets joined as always. Thick paper, wide margins, no imperfections or restorations. Delicate original colour of the continents, which is exceptionally rare for this map of the world. With the proper High Crown watermark, Basle 1530s, which is essential for this woodcut map that is known for forgeries and reproductions on old paper. Pristine collector's condition.

The Mapping of the World

No imprint or date appears on this large and decorative map in two sheets which was first printed with the 1532 Basle edition of the Novus Orbis Regionum by Johann Huttich and Simon Grynaeus. Sebastian Münster contributed a long introduction Typi Cosmographici et Declaratio et usus to their collection of voyages, and there have been arguments for and against his authorship of the accompanying map. It seems most probable that the map itself is Münster's whereas the decor is more frequently attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger who was co-operating with several Basle publishers at the time.

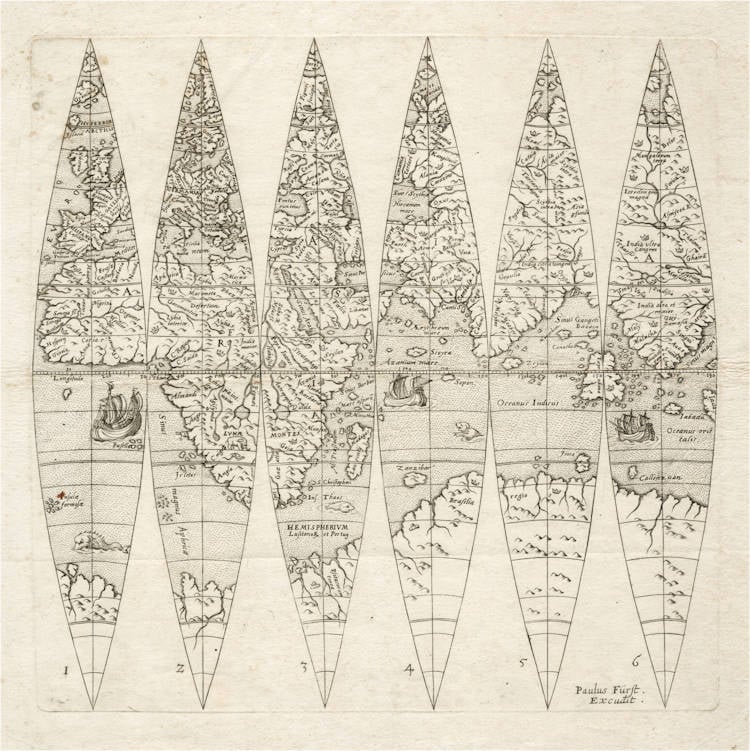

Geographically the map is quite antiquated and was probably prepared prior to 1532 based partly on the world configuration depicted in the Schöner globes, or on Apian's map of 1520. As no southern continent is shown Nordenskiöld assumed that the map compiler was unaware of the first circumnavigation of the globe made in 1522 but his contention cannot be supported. The projection follows the oval one of Bordone, with two cherubs energetically turning crank handles at the north and south poles.

What the Münster-Holbein map lacks in precision it gains in richness of artistic decoration. Huge sea-monsters, mermaids, and an early high-pooped galleon embellish the oceans. The surrounding border to the map is filled with vivid vignettes of real or outlandish local scenes --- winged serpents, grotesquely big-lipped natives, hunting scenes and feasting cannibals.

The version of the map normally associated with the earlier printings has the names of the continents Asia, Africa, and Europe in moderately large capitals. Later printings tend to have Asia in particularly large letters. In another version Tropicus Capricorni is printed below rather than above the tropical line. Various other differences in typesetting, in the width of the title, and in the composition of the text in the panels are known. The Paris edition of the Novus Orbis Regionum, published in July 1532, contains the quite different map by Oronce Fine described in the previous entry. Later Basle editions of 1537 and 1555 have the Münster- Holbein map but there is not normally any map in the editions of 1534 and 1563 unless an appropriate loose map has been inserted after publication.

As with Fine's map, excellent facsimiles have been made of the Basle map, and these are often bound in copies of the Novus Orbis Regionum to replace original maps which have been removed. Considerable care is needed to distinguish some recent facsimiles as they have been printed on old paper and have been folded and aged to correspond with all the expected characteristics of a genuine contemporary woodcut.

BL 985.h.17. Harrisse 198-199; Nordenskiöld, pp. 105-106 and plate XIII; Sabin 34100; TWE 65.

(Rodney Shirley map 67)

Sebastian Münster (1489-1552)

Following the various editions of Waldseemüller's maps, the names of three cartographers dominate the sixteenth century: Mercator, Ortelius and Münster, and of these three Münster probably had the widest influence in spreading geographical knowledge throughout Europe in the middle years of the century.

His Cosmographia, issued in 1544, contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of detail about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time, going through nearly forty editions in six languages.

An eminent German mathematician and linguist, Münster became Professor of Hebrew at Heidelberg and later at Basle, where he settled in 1529. In 1528, following his first mapping of Germany, he appealed to German scholars to send him "descriptions, so that all Germany with its villages, towns, trades, etc. may be seen as in a mirror", even going so far as to give instructions on how they should "map" their own localities. The response was far greater than expected and such information was sent by foreigners as well as Germans so that, eventually, he was able to include many up-to-date, if not very accurate, maps in his atlases.

He was the first to provide a separate map of each of the four known Continents and the first separately printed map of England. His maps, printed from woodblocks, are now greatly valued by collectors. His two major works, the Geographia and the Cosmographia were published in Basle by his step-son, Henri Petri, who continued to issue many editions after Münster's death of the plague in 1552.

(Moreland & Bannister).

The remaining modern maps, [...], are all drawn on a plane projection, undergraduated, without scales, and variously oriented with north, south, east or west at the top, "without the excuse of topographical necessity", as Nordenskjöld severely remarks. In spite of these and other cartographic defects, they constitute an important corpus of geographical knowledge and interpretation; Münster was the first atlas-maker to furnish separate maps of the four continents then known; and for England, Scandinavia and southern Germany, eastern Europe and America he brought recent and significant representations into general currency.

(Skelton).

The Cosmographia of Sebastian Münster must rank as the greatest geographical compendium of the period - an immensely detailed work illustrated with woodcut portraits, scenes, town plans and panoramas, and maps. Born in 1488, Münster was a Fransiscan who became Professor of Hebrew at Heidelberg and later at Basle, where he taught Hebrew and, amongst other works, published the first German translation of the Bible from Hebrew. In 1540 his edition of Ptolemy's Geographia was published, followed in 1544 by the Cosmographia Universalis. Together these ran to over 35 editions published mostly in Basle in Latin, German, French and Italian versions. Münster's particular cartographic importance lies in the number of 'new' maps he introduced and, above all, in the innovative, separate mapping of each of the four continents. The map of the Americas is not only the first map to show the Western Hemisphere separately, but is also the first to show North and South America joined together.

(Potter p38).

Sebastian Münster was raised as a Franciscan monk, converted to Lutheranism, taught Hebrew at Heidelberg and Basle, and was proficient in Greek and some Asian tongues. He died of the plague in 1552. First published in 1540, his atlas was the first to contain separate maps of each of the four continents.

(Suárez).

In 1540 Sebastian Münster, who was to become one of the most influential cartographers in the sixteenth century, published his edition of Ptolemy's Geographia with a further section of modern, more up-to-date maps. He included for the first time a set of continental maps, the America was the earliest of any note. Münster studied Hebrew at Heidelberg and was a scholar of geography, writing amongst other works the Polyhistor.

He was one of the first to create space in the woodblock for the insertion of place-names in metal type. The map's inclusion in Münster's Cosmography, first published in 1544, sealed the fate of "America" as the name for the New World. The book proved to be very popular, there being nearly forty editions during the following 100 years.

(Burden).

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543)

Holbein was one of the most accomplished portraitists of the 16th century. He spent two periods of his life in England (1526-8 and 1532-43), portraying the nobility of the Tudor court. Holbein's famous portrait of Henry VIII (London, National Portrait Gallery) dates from the second of these periods. 'The Ambassadors', also from this period, depicts two visitors to the court of Henry VIII. 'Christina of Denmark' is a portrait of a potential wife for the king.

Holbein was born in Augsburg in southern Germany in the winter of 1497-8. He was taught by his father, Hans Holbein the Elder. He became a member of the Basel artists' guild in 1519. He travelled a great deal, and is recorded in Lucerne, northern Italy and France. In these years he produced woodcuts and fresco designs as well as panel paintings. With the spread of the Reformation in Northern Europe the demand for religious images declined and artists sought alternative work. Holbein first travelled to England in 1526 with a recommendation to Thomas More from the scholar Erasmus. In 1532 he settled in England, dying of the plague in London in 1543.

Holbein was a highly versatile and technically accomplished artist who worked in different media. He also designed jewellery and metalwork.

(The National Gallery)

Related Categories

Related Items