Leen Helmink Antique Maps

The Portuguese discovery of the sea route to the Indian Ocean (3 maps)

Stock number: 19076

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

Title

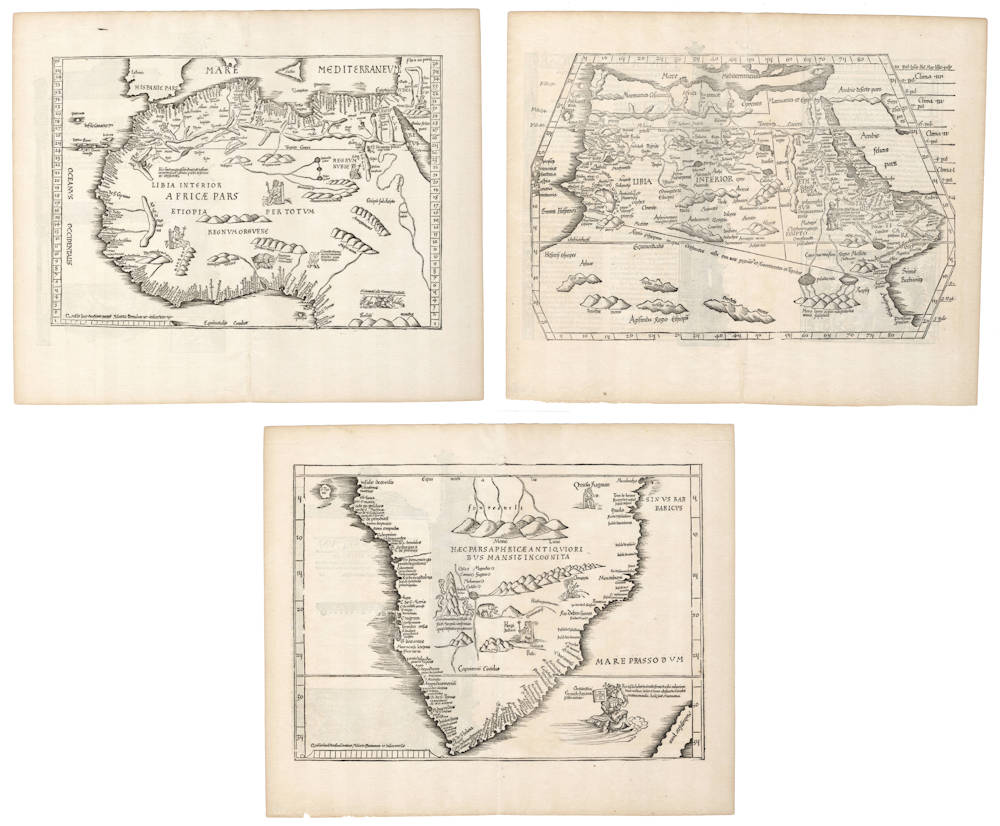

Tabula Moderna Primae partis Africae, Tabula Moderna Secundae partis Africae, Tabula III Aphricae

First Published

Strassburg, 1522

This Edition

1525 second edition

Size

each ca 27.7 x 40.3 cms

Technique

Condition

pristine

Price

$ 3,750.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

Enter Vasco da Gama

Uniform set of three extremely early explorer maps that present the Portuguese exploration and discovery of the sea route to the Indies. The maps are icons from the age of exploration.

From the rare 1525 Strassburg edition. The woodcut decorations on the back are attributed to Albrecht Dürer, who also made the woodcut of the armillary sphere in this atlas.

Like many maps in Fries' atlas, cartographically these maps are slightly reduced versions of corresponding maps in Martin Waldseemüller's atlas of 1513. But while the Waldseemuller are spartan in nature, Laurent Fries has added fascinating text legends and decorations that come from Waldseemüller's 1516 updated wall map of the world that had been published in the meantime. Of special interest is the image of Portugal's King Manuel riding a sea monster near the southern tip of Africa. His control of the sea monster expresses Portugal’s confidence in navigating the ocean, as well as Portugal’s mastery of the sea route to India around the Cape of Good Hope, pioneered by Vasco da Gama.

Condition

Uniform set. Strong early impressions of the woodblocks. Thick and clean paper. Minimal shine through of the verso text and woodcuts as always. Ample margins all around. No restorations or imperfections. Exceptional look and feel. Pristine collector's condition of three uniform items from the dawn of the charting of the earth.

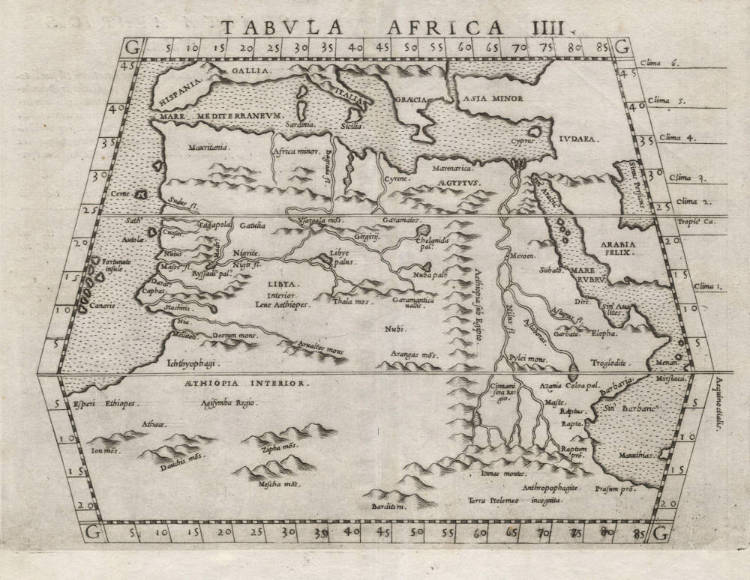

The corresponding 1513 Waldseemüller versions of these maps

Tabula Moderna Prime Partis Aphricae

Tabula Moderna Secunde Porciones Aphrice

Tabula Quarta Africae

Nordensjköld on the 1513 progenitors

The most important maps in the Ptolemy of 1513, however, are the two maps of Africa in double-folio which I have reproduced here. They form admirable though hitherto completely neglected illustrations of one of the most important episodes in the history of Navigation, and they are evidently directly based on carefully registered observations during the Portuguese exploring voyages round Africa to India.

For their exactness, and in the richness of names along the coasts of Africa, these maps are comparable with the old portolanos of the Mediterranean Sea.

The corresponding map of Asia [as well as the Fries version of it] shows on the contrary that the geographical notions about the Indian Peninsulas when the map was drawn (1507?) were still very vague in Europe, and dependent on hearsay.

(Nordenskjöld)

Map 1: First modern map of Africa north of the equator.

"This map is [a reduced version of the map] from Waldseemüller's Ptolemy atlas of 1513. As northern Africa was better known than southern Africa at that period it has more geographical information, especially in the interior. Various kingdoms are described, with a multitude of coastal names, and as with the southern part these are placed within the coastline. The Mediterranean and Red Sea are prominently featured as well as a number of islands on the northwest coast - Madeira, the Canaries, etc. - which at that time were already well known to the Portuguese in their initial efforts to discover a route to the Indies."

(Norwich on the 1513 version).

"Prior to 1513 any printed maps showing the North African coastline had been based on the ancient Ptolemaic geography. Here, Waldseemüller has made use of Portuguese reports to give more detail and a better outline than before for the western coasts. During the previous century the Portuguese, under Prince Henry, had gradually travelled further south - Cape Bojador, just south of the Tropic of Cancer, had been passed in 1434; Cape Verde was reached in 1444; and, after a halt in voyages, by 1481 the Equator had been traversed; only seven years later, Dias rounded the Cape."

(Potter on the 1513 version).

Map 2: First modern map of Africa south of the equator.

"This fine woodcut map of South Africa depicts the area from the equator to the Cape of Good Hope, together with most of Madagascar. The coastline is full of names of rivers and bays, printed inland from the coast, using many of Portuguese origin. The prominent central mountain range is called Mons Lune and described as the origin of the Nile."

(Norwich on the 1513 version).

"This reissued map [after Waldseemüller 1513] now has three kings on their thrones, an elephant, a cockatrice and two serpents next to a sugarloaf mountain, while the king of Portugal rides a bridled sea monster on the Mare Prassodum, holding the banner of Portugal in his right hand and the sceptre in his left. Mountains are added and inland rivers appear to the south of the Mountains of the Moon."

(Norwich).

"A fascinating reissue of Waldseemüller's map - the first of South Africa."

(Potter).

Map 3: Ptolemy's overview map of Africa.

To complete the set of modern maps that reveal the latest Portuguese explorations and the new found gateway into the Indian Ocean, the Ptolemaic overview map of Africa gives Ptolemy's refuted view of Africa attached to the southland and a landlocked Indian Ocean.

Fries map is a reduced version of the Waldseemuller 1513 Ptolemaic overview map of Africa.

The text legends on the maps

For detailed transcriptions and translations of the Latin text legends on this map, as well as the sources for them, please do not hesitate to ask us.

Laurent Fries (c.1490-c.1532)

Laurent Fries (Laurentius Frisius), born in Mulhouse in Burgundy, travelled widely, studying as a physician and mathematician in Vienne, Padua, Montpellier and Colmar before settling in Strassburg. There he is first heard of working as a draughtsman on Peter Apian's highly decorative cordiform World Map, published in 1520. Apian’s map was based on Waldseemüller's map of 1507 which no doubt inspired Fries's interest in the Waldseemüller Ptolemy atlases of 1513 and 1520 and brought him into contact with the publisher, Johannes Grüninger. It is thought that Grüninger had acquired the woodcuts of the 1520 edition with the intention of producing a new version to be edited by Fries. Under his direction the maps were redrawn and although many of them were unchanged, except for size, others were embellished with historical notes and figures, legends and the occasional sea monster. Three new maps were added.

There were four editions of Fries' reduced sized re-issue of Waldseemüller's Ptolemy atlas:

1522 Strassburg: 50 woodcut maps, reduced in size, revised by Laurent Fries (Laurentius Frisius) and included the earliest map showing the name ‘America' which is likely to be available to collectors

1525 Strassburg: re-issue of 1522 maps

1535 Lyon: re-issue of 1522 maps, edited by Michael Servetus who was subsequently tried for heresy and burned at the stake in 1553, ostensibly because of derogatory comments in the atlas about the Holy Land – the fact that the notes in question had not even been written by Servetus, but were copied from earlier editions, left his Calvinist persecutors unmoved

1541 Vienne (Dauphiné): re-issue of the Lyon edition - the offensive comments about the Holy Land have been deleted

(Moreland and Bannister)

Martin Waldseemüller (c.1470-1518)

Waldseemüller, born in Radolfzell, a village on what is now the Swiss shore of Lake Constance, studied for the church at Freiburg and eventually settled in St Dié at the Court of the Duke of Lorraine, at that time a noted patron of the arts. There, in the company of likeminded savants, he devoted himself to a study of cartography and cosmography, the outcome of which was a world map on 12 sheets, now famous as the map on which the name “America’ appears for the first time. Suggested by Waldseemüller in honour of Amerigo Vespucci (latinised: Americus Vesputius) whom he regarded, quite inexplicably, as the discoverer of the New World, the new name became generally accepted by geographers before the error could be rectified, and its use was endorsed by Mercator on his world map printed in 1538. Although only one copy is now known of Waldseemüller's map and of the later Carta Marina (1516) they were extensively copied in various forms by other cartographers of the day.

Waldseemüller is best known for his preparation from about 1507 onwards of the maps for an issue of Ptolemy's Geographia, now regarded as the most important edition of that work. Published by other hands in Strassburg in 1513, it included 20 ‘modern' maps and passed through one other edition in 1520. Four more editions on reduced size were issued of the Laurent Fries version.

It remained the most authoritative work of its time until the issue of Münster's Geographia in 1940 and Cosmographia in 1544.

(Moreland and Bannister)

Claudius Ptolemy (c.100 - c.170)

Ptolemy, Latin in full Claudius Ptolemaeus waS an Egyptian astronomer, mathematician, and geographer of Greek descent who flourished in Alexandria during the 2nd century AD. In several fields his writings represent the culminating achievement of Greco-Roman science, particularly his geocentric (Earth-centred) model of the universe now known as the Ptolemaic system.

Virtually nothing is known about Ptolemy’s life except what can be inferred from his writings. His first major astronomical work, the Almagest, was completed about 150 ce and contains reports of astronomical observations that Ptolemy had made over the preceding quarter of a century. The size and content of his subsequent literary production suggests that he lived until about 170 AD.

Astronomer

The book that is now generally known as the Almagest (from a hybrid of Arabic and Greek, “the greatest”) was called by Ptolemy Hē mathēmatikē syntaxis (“The Mathematical Collection”) because he believed that its subject, the motions of the heavenly bodies, could be explained in mathematical terms.

Mathematician

Ptolemy has a prominent place in the history of mathematics primarily because of the mathematical methods he applied to astronomical problems. His contributions to trigonometry are especially important. For instance, Ptolemy’s table of the lengths of chords in a circle is the earliest surviving table of a trigonometric function. He also applied fundamental theorems in spherical trigonometry (apparently discovered half a century earlier by Menelaus of Alexandria) to the solution of many basic astronomical problems.

Among Ptolemy’s earliest treatises, the Harmonics investigated musical theory while steering a middle course between an extreme empiricism and the mystical arithmetical speculations associated with Pythagoreanism. Ptolemy’s discussion of the roles of reason and the senses in acquiring scientific knowledge have bearing beyond music theory.

Geographer

Ptolemy’s fame as a geographer is hardly less than his fame as an astronomer. Geōgraphikē hyphēgēsis (Guide to Geography) provided all the information and techniques required to draw maps of the portion of the world known by Ptolemy’s contemporaries. By his own admission, Ptolemy did not attempt to collect and sift all the geographical data on which his maps were based. Instead, he based them on the maps and writings of Marinus of Tyre (c. 100 ce), only selectively introducing more current information, chiefly concerning the Asian and African coasts of the Indian Ocean. Nothing would be known about Marinus if Ptolemy had not preserved the substance of his cartographical work.

Ptolemy’s most important geographical innovation was to record longitudes and latitudes in degrees for roughly 8,000 locations on his world map, making it possible to make an exact duplicate of his map. Hence, we possess a clear and detailed image of the inhabited world as it was known to a resident of the Roman Empire at its height—a world that extended from the Shetland Islands in the north to the sources of the Nile in the south, from the Canary Islands in the west to China and Southeast Asia in the east. Ptolemy’s map is seriously distorted in size and orientation compared with modern maps, a reflection of the incomplete and inaccurate descriptions of road systems and trade routes at his disposal.

Ptolemy also devised two ways of drawing a grid of lines on a flat map to represent the circles of latitude and longitude on the globe. His grid gives a visual impression of Earth’s spherical surface and also, to a limited extent, preserves the proportionality of distances. The more sophisticated of these map projections, using circular arcs to represent both parallels and meridians, anticipated later area-preserving projections. Ptolemy’s geographical work was almost unknown in Europe until about 1300, when Byzantine scholars began producing many manuscript copies, several of them illustrated with expert reconstructions of Ptolemy’s maps. The Italian Jacopo d’Angelo translated the work into Latin in 1406. The numerous Latin manuscripts and early print editions of Ptolemy’s Guide to Geography, most of them accompanied by maps, attest to the profound impression this work made upon its rediscovery by Renaissance humanists.

(Britannica)