Leen Helmink Antique Maps & Atlases

www.helmink.com

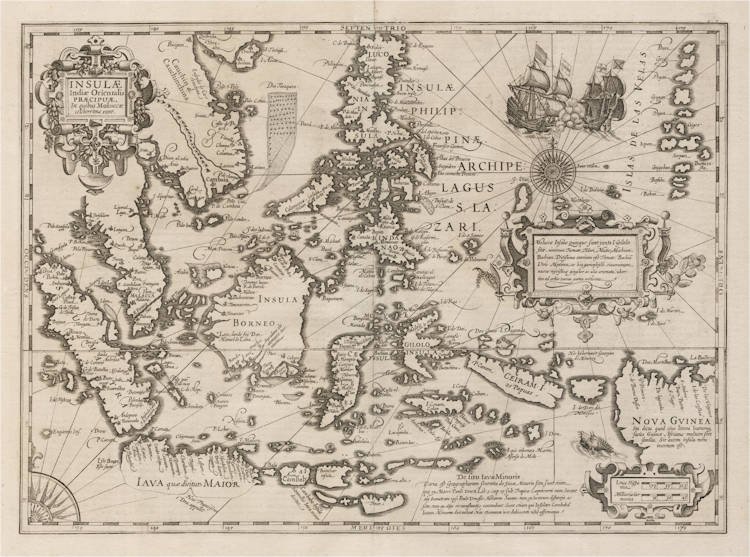

Jodocus Hondius I - Insulae Indiae Orientalis

Certificate of Authentication

This is to certify that the item illustrated and described below is a genuine and

original antique map or print that was published on or near the given date.

Dr Leendert Helmink, Ph.D.

Cartographer

Jodocus Hondius

First Published

Amsterdam, 1606

This edition

1623 Latin

Size

34.0 x 48.0 cms

Technique

Copperplate engraving

Stock number

19131

Condition

excellent

Description

A supreme example from the 1623 Latin edition of the atlas.

An excellent example. Wide margins, clean and thick paper, which is highly unusual for maps from this atlas. Paper with beautiful patina of the centuries. A crisp and even imprint of the copperplate. An excellent collector's example of this legendary map of the area.

Spectacular map of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Philippines, with important improvements by Gerard Mercator and Jodocus Hondius. The south coast of Java is uncertain and locates the landfall of Francis Drake in 1578.

New Guinea has a text legend that states that it may be an island or part of a great Southern Continent. A spectacular battle between Dutch and Spanish vessels is shown, believed to refer to the vicious encounter off Manilla Bay in 1600 between Olivier van Noort and Dr. de Morga. The region was the theater of bitter naval battles between the Dutch, the Portuguese, and the Spanish Empire.

Three beautiful cartouches compliment this splendid map. The Moluccas islands are listed, with the remark that they are exporting all over the world a great abundance of fragrant spices. In the lower center is a text referring to Marco Polo's earliest description of these regions. The map has been engraved by Jodocus Hondius the Elder, the best copperplate engraver at the time.

"The map may be considered the most elegant and decorative map of the region, including all of the Indies and the Philippines, extending as far east as New Guinea."

(Suárez).

Jodocus Hondius and Francis Drake

Two beautiful new maps of Southeast Asia were created by the Dutch mapmaker Jodocus Hondius for an enlarged issue of the Mercator Atlas of 1606. One covered the Indian Ocean region (India Orientalis), and the other focused on the islands (Insula India Orientalis, Præcipua, In quibus Molucca celeberrima sunt). For their artistic character and engraving style, these splendid maps better represent the concluding chapter of the sixteenth century rather than the dawn of the seventeenth. Geographically, Hondius largely followed the Bartolomeu Lasso pattern, adopting many of its idiosyncrasies, such as the Enseada de Cochinchina (Bay of Cochinchina = Gulf of Tongkin) with an exaggerated rendering of the Red River Delta. Hondius adds, however, a bit from his own notebook.

The Insula India Orientalis is one of few maps to show any trace of Francis Drake's presence in Southeast Asia. Hondius had spent several years in London, having fled there in about 1583 to avoid religious persecution. At that time, Francis Drake's flamboyant circumnavigation was still fresh news, and Hondius (as we know from other maps he made) became well-acquainted with the voyage. Drake is believed to have taken with him a sea chart prepared by a Lisbon maker, possibly Vaz Dourado. To this manuscript chart and other printed materials, he added Iberian sea charts and pilot books, plundered en route. Like Magellan before him, his only predecessor in circumnavigation, Drake's first landfall in Southeast Asia was some point in Micronesia (the precise landfall is calmly disputed, although Palau is the most likely candidate). Unlike Magellan, he had set off across the Pacific from some point in North America (that landfall is hotly disputed). From Micronesia he continued west to Mindanao, then sailed southeast in search of the Spiceries. He picked up two native fishermen in canoes in the seas somewhere northeast of Sulawesi, who guided him to the Moluccas. Leaving the Moluccas filled with spices and the precious spoils of earlier plunder in South America, Drake attempted to navigate the tricky waters leading to the clearer seas to the south, but ran aground on a steep reef off Sulawesi. Three tons of cloves, among other valuables, were dumped overboard to lessen their weight, but nothing seemed to help them from what appeared to be inescapable disaster until the strong winds reversed, freeing them from the reef. Hondius seems to recognize the fact that the eastern Sulawesi coastline was far more complex than current charts showed. Although he does not know what configuration to give the island, he 'ripples' the eastern shores of Sulawesi in a more pronounced fashion than Lasso, acknowledging that there were significant, though unknown, undulations in the coast, such as that which befouled Drake.

Drake and his crew eventually found their way out of the maze of islands in the Molucca and Banda Seas, assisted by local sailors. After crossing into clear ocean by way of Timor, Drake made landfall somewhere on the southern coast of Java, probably in the vicinity of Tjilatjap (Cilacap). Drake is the first European known to have made landfall on the southern coast of Java.

Hondius notes this important event on the Insula India Orientalis. He draws the southern coast of Java only as a dotted (hypothetical) line, save for a port at about the coast's midpoint, which is shown with a solid line. He inscribes Huc Franciscus Dra. appulit on the port, thus recording that Drake had landed there. A separately-published world map of Hondius, which was probably published in Amsterdam in about 1595, contained insets depicting Drake's south Java landing, his reception by the king of the Moluccas, and his near-catastrophic accident on the reefs near Sulawesi.

Hondius marks the island east of Bali as Cambaba (Sumbawa), though it should actually be Lombok; like Linschoten, he identifies it as having been the java minor of old. The islands further east are abbreviated even more than on the Lasso model. One new term is Buena vista (good view) to denote the island of Tinian, north of Guam, possibly taken from one of the Spanish charts pillaged by Drake. Due west of Guam, just to the right of the compass rose, is the island of Saia vedra, a reference to the Spanish captain Saavedra, who sailed to the Philippines from Mexico in 1527; use of his name to denote an island is also found on the Herrera y Tordesillas /López de Velasco map as the island of Sahavedra.

(Suarez)

Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612)

Jodocus Hondius the Younger (son) (1594-1629)

Henricus Hondius (son) (1597-1651)

Jodocus Hondius the Elder, one of the most notable engravers of his time, is known for his work in association with many of the cartographers and publishers prominent at the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century.

A native of Flanders, he grew up in Ghent, apprenticed as an instrument and globe maker and map engraver. In 1584, to escape the religious troubles sweeping the Low Countries at that time, he fled to London where he spent some years before finally settling in Amsterdam about 1593. In the London period he came into contact with the leading scientists and geographers of the day and engraved maps in The Mariner's Mirrour, the English edition of Waghenaer's Sea Atlas, as well as others with Pieter van den Keere, his brother-in-law. No doubt his temporary exile in London stood him in good stead, earning him an international reputation, for it could have been no accident that Speed chose Hondius to engrave the plates for the maps in The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine in the years between 1605 and 1610.

In 1604 Hondius bought the plates of Mercator's Atlas which, in spite of its excellence, had not competed successfully with the continuing demand for the Ortelius Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. To meet this competition Hondius added about 40 maps to Mercator's original number and from 1606 published enlarged editions in many languages, still under Mercator's name but with his own name as publisher. These atlases have become known as the Mercator/ Hondius series. The following year the maps were re-engraved in miniature form and issued as a pocket Atlas Minor.

After the death of Jodocus Hondius the Elder in 1612, work on the two atlases, folio and miniature, was carried on by his widow and sons, Jodocus II and Henricus, and eventually in conjunction with Jan Jansson in Amsterdam. In all, from 1606 onwards, nearly 50 editions with increasing numbers of maps with texts in the main European languages were printed.

(Moreland and Bannister)