Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Old books, maps and prints by Thomas Fletcher Waghorn

Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800 - 1850)

Thomas Waghorn: Controversial Visionary of Global Transportation

Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800 - 1850) was during his day a very famous and controversial figure. To some, he was a charismatic visionary, years ahead of his time. To others, he was a self-aggrandizing confidence man – the truth perhaps is that he was both these things!

A native of Snodland, Kent, Waghorn joined the Royal Navy at the age of 12 and sailed the world, with particular experience in the East Indies. He became obsessed with shortening the monstrously long and unpleasant route from England to India that went via the Cape of Good Hope. As early as 1829-30, he claimed to have investigated a route from England to India the traversed Egypt’s Suez Isthmus, so reducing the travel distance by 5,000 miles, and the time from four months to 35-45 days. In 1832, Waghorn resigned from the navy, with the rank of Lieutenant, and dedicated himself to opening an England-Egypt-India route for commercial purposes.

Waghorn made several trips from England to India via Egypt, and even lived with the Arab tribes around Suez for two years in order to gain knowledge and local ‘street cred’. He also struck up a good relationship with Ibrahim Pasha, the ruler of Egypt, who supported of his plans.

In 1837, Waghorn founded a firm that transported mail and a limited number of passengers across the Suez, connecting them to steamship lines on both sides, so creating a fast connection between England and India. He also benefitted from being appointed Britain’s Deputy Consul in Egypt (albeit a post he held only for a short time, as he quarreled with his superiors).

For a time Waghorn’s enterprise appeared to be quite successful, as his route was considered the ‘gold standard’ for the fast transport of the post and important government communications between India and the home country. However, his business suffered when from 1840 the shipping behemoth P&O set up a rival service over the Suez, and it was taken out entirely in 1844 when 300 of his horses died of a plague. Waghorn then promptly sold what remained of his Egyptian assets and privileges to Ibrahim Pasha.

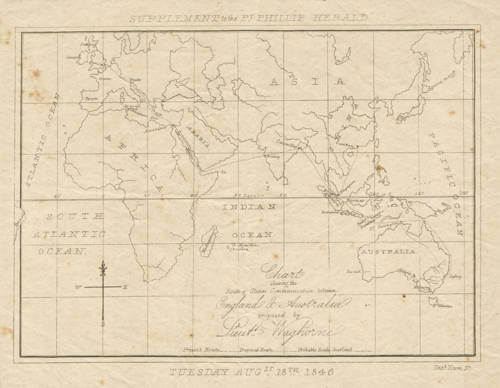

However, the failure of Waghorn’s Egyptian enterprise did little to dampen his enthusiasm for global transport and communications. He noticed that while the England-Suez-India connection was being well served, the onward trip to Australia was not well developed. Hitherto, most voyages from England to Australia travelled via the Cape of Good Hope and across the southern Indian Ocean, a brutal trip that usually lasted four months. Waghorn had a vision to halve the travel time, and made many proposals to the Crown to convince them to subsidize a steamship line from Singapore to Sydney. While these proposals gained a tremendous amount of attention in both London and in Australia, Waghorn failed to

secure the notoriously parsimonious government’s support.

As a consolation prize, the Crown agreed to pay for Waghorn to investigate an improved overland route across Europe (from Calais to Trieste), connecting to the Suez, so knocking time off the England-India run. Waghorn duly invested in several trans-European trials. Sadly, though, the government apparently did not follow through on the promised funds, leaving Waghorn £5,000 in debt – a large sum for the time.

Stressed by his constant travels and financial issues, Thomas Waghorn died suddenly in London at the age of 49.

However, Waghorn had a legacy that far outlived him. Dueling historians have debated whether Waghorn was a serious entrepreneur with credible, if not visionary, business plans for revolutionizing global travel, or, conversely, that he was huckster who knowingly exaggerated the viability of his schemes to bilk both the Crown and private investors. In any event, Waghorn was incredibly influential, for he drove the conversation that ultimately led to dramatic material improvements in travel between England, India and Down Under in the years after his death. Ferdinand de Lesseps, the man who completed the Suez Canal 1869, revered Waghorn, even erecting a statue to him in Egypt bearing the line “he opened the route, and we followed him”.