Leen Helmink Antique Maps

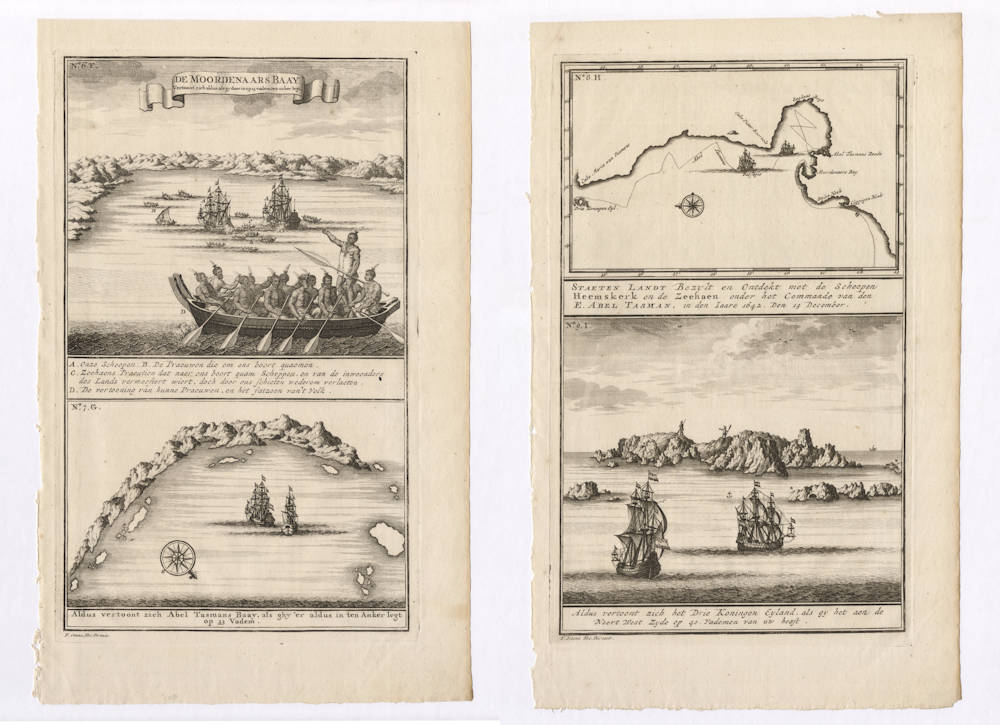

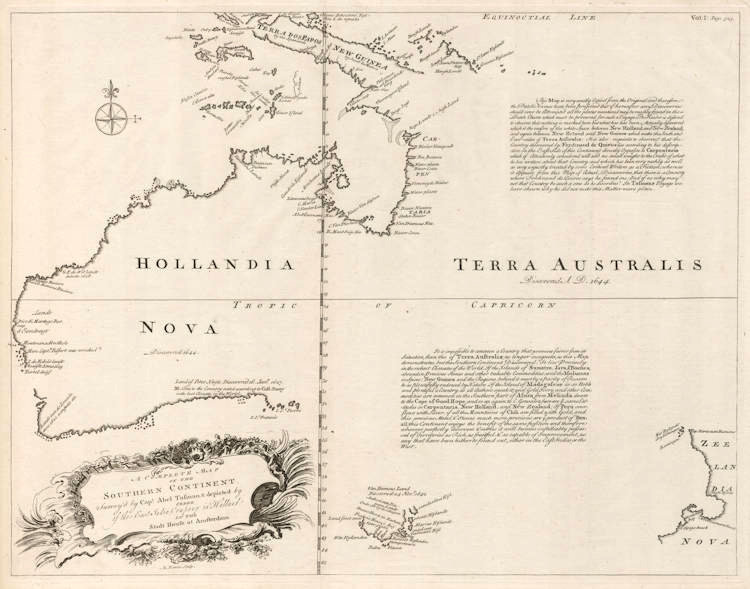

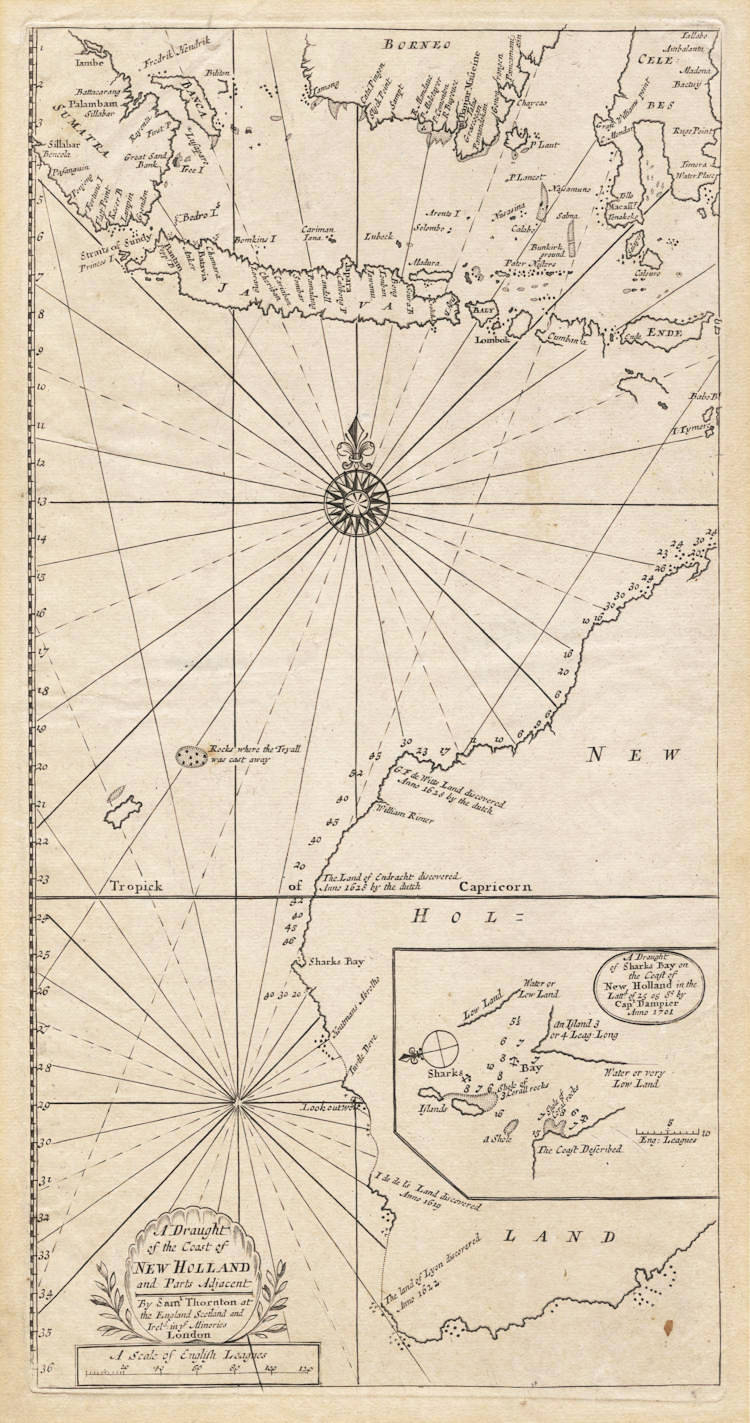

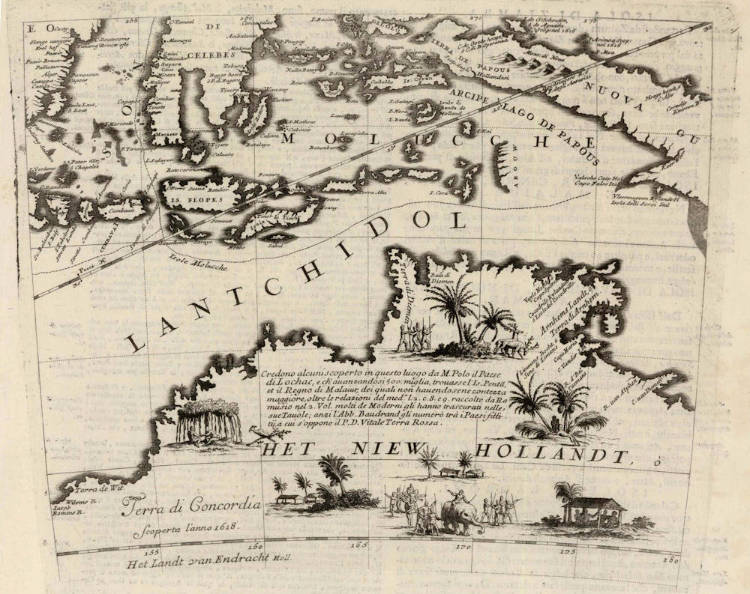

Tasman's discovery of New Zealand by Valentijn

Stock number: 19056

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

François Valentijn (biography)

Title

De Moordenaars Baay

First Published

Amsterdam, 1726

This Edition

1726

Technique

Condition

pristine

Price

$ 3,250.00

(Convert price to other currencies)

Description

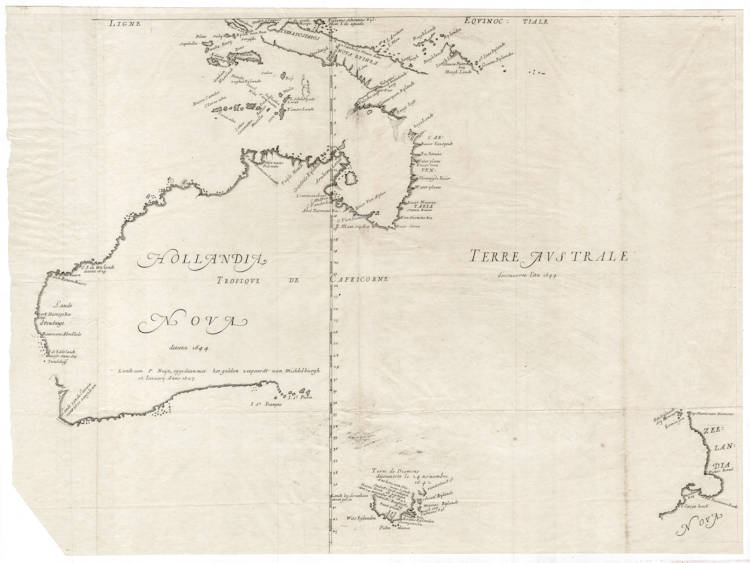

Valentijn's copper engravings of Tasman's 1642 discovery of New Zealand.

Condition

Strong and early imprints of the copperplates. Good paper margins. Mint collector's condition.

Source

Valentijn has copied the charts, coastal profiles and legends from Abel Tasman's journal, now in the Dutch National Archives. The journal is reproduced online here by the National Library of Australia.

Below are the entries on the discovery of New Zealand, from the English translation of Tasman's original journal by J.E. Heeres, published in 1898.

ABEL JANSZOON TASMAN'S JOURNAL in the The Hague Archives

[December 1642]

Item the 6th [of December].

In the morning the wind from the south-west with a light breeze; at noon we were in Latitude 41° 15', Longitude 172° 35'; course kept east, sailed 40 miles; the weather was quite calm and still all the afternoon, the sea running high from all quarters but especially from the south-west; in the evening when the watches were setting we got a steady breeze from the east-north-east and north-east.

Item the 7th.

The wind still continuing to blow from the north-east, the breeze quite as fresh as during the night. At noon Latitude estimated 42° 13', Longitude 174° 31'; course kept south-east by east, sailed 26 miles. Variation increasing 5° 45' North-West.

Item the 8th.

During the night we had a calm, the wind going round to the west and north-west. At noon Latitude estimated 42° 29', Longitude 176° 17'; course kept east by south, sailed 20 miles.

Item the 9th.

We drifted in a calm so that by estimation we were carried 3 miles to the south-eastward. At noon Latitude observed 42° 37', Longitude 176° 29'. Variation 5°. Towards evening we had a light breeze from the west-north-west.

Item the 10th.

Occasional squalls of rain mixed with hail, the wind being westerly with a top-gallant gale. At noon Latitude observed 42° 45', Longitude 178° 40'; course kept east, sailed 24 miles.

Item the 11th.

Good weather with a clear sky and a westerly wind with a top-gallant gale. At noon Latitude observed 42° 48', Longitude 181° 51'; course kept east, sailed 38 miles. Variation increasing 7° North-East.

Item the 12th.

Good weather, the wind blowing from the south-south-west and south-west with a steady breeze. At noon Latitude observed 42° 38', Longitude 185° 17'; course kept east, sailed 38 miles. The heavy swells continuing from the south-west, there is no mainland to be expected here to southward. Variation 7° North-East.

Item the 13th.

Latitude observed 42° 10', Longitude 188° 28'; course kept east by north, sailed 36 miles in a south-south-westerly wind with a top-gallant gale. Towards noon we saw a large, high-lying land, bearing south-east of us at about 15 miles distance; we turned our course to the south-east, making straight for this land, fired a gun and in the afternoon hoisted the white flag, upon which the officers of the Zeehaan came on board of us, with whom we resolved to touch at the said land as quickly as at all possible, for such reasons as are more amply set forth in this day's resolution. In the evening we deemed it best and gave orders accordingly to our steersmen to stick to the south-east course while the weather keeps quiet but, should the breeze freshen, to steer due east in order to avoid running on shore, and to preclude accidents as much as in us lies; since we opine that the land should not be touched at from this side on account of the high open sea running there in huge hollow waves and heavy swells, unless there should happen to be safe land-locked bays on this side. At the expiration of four glasses of the first watch we shaped our course due east. Variation 7° 30' North-East.

Item the 14th.

At noon Latitude observed 42° 10', Longitude 189° 3'; course kept east, sailed 12 miles. We were about 2 miles off the coast, which showed as a very high double land, but we could not see the summits of the mountains owing to thick clouds. We shaped our course to northward along the coast, so near to it that we could constantly see the surf break on the shore. In the afternoon we took soundings at about 2 miles distance from the coast in 55 fathom, a sticky sandy soil, after which it fell a calm. Towards evening we saw a low-lying point north-east by north of us, at about 3 miles distance; the greater part of the time we were drifting in a calm towards the said point; in the middle of the afternoon we took soundings in 45 fathom, a sticky sandy bottom. The whole night we drifted in a calm, the sea running from the west-north-west, so that we got near the land in 28 fathom, good anchoring-ground, where, on account of the calm, and for fear of drifting nearer to the shore, we ran out our kedge-anchor during the day-watch, and we are now waiting for the land-wind.

Item the 15th.

In the morning with a light breeze blowing from the land we weighed anchor and did our best to run out to sea a little, our course being north-west by north; we then had the northernmost low-lying point of the day before, north-north-east and north-east by north of us. This land consists of a high double mountain-range, not lower than Ilha Formoza. At noon Latitude observed 41° 40', Longitude 189° 49'; course kept north-north-east, sailed 8 miles; the point we had seen the day before now lay south-east of us, at 2½ miles distance; northward from this point extends a large rocky reef; on this reef, projecting from the sea, there are a number of high steep cliffs resembling steeples or sails; one mile west of this point we could sound no bottom. As we still saw this high land extend to north-north-east of us we from here held our course due north with good, dry weather and smooth water. From the said low point with the cliffs, the land makes a large curve to the north-east, trending first due east, and afterwards due north again. The point aforesaid is in Latitude 41° 50' south. The wind was blowing from the west. It was easy to see here that in these parts the land must be very desolate; we saw no human beings nor any smoke rising; nor can the people here have any boats, since we did not see any signs of them; in the evening we found 8° North-East variation of the compass.

Item the 16th.

At six glasses before the day we took soundings in 60 fathom anchoring-ground. The northernmost point we had in sight then bore from us north-east by east, at three miles distance, and the nearest land lay south-east of us at 1½ miles distance. We drifted in a calm, with good weather and smooth water; at noon Latitude observed 40° 58', average Longitude 189° 54'; course kept north-north-east, sailed 11 miles; we drifted in a calm the whole afternoon; in the evening at sunset we had 9° 23' increasing North-East variation; the wind then went round to south-west with a freshening breeze; we found the furthest point of the land that we could see to bear from us east by north, the land falling off so abruptly there that we did not doubt that this was the farthest extremity. We now convened our council with the second mates, with whom we resolved to run north-east and east-north-east till the end of the first watch, and then to sail near the wind, wind and weather not changing, as may in extenso be seen from this day's resolution. During the night in the sixth glass it fell calm again so that we stuck to the east-north-east course; although in the fifth glass of the dog-watch, we had the point we had seen in the evening, south-east of us, we could not sail higher than east-north-east slightly easterly owing to the sharpness of the wind; in the first watch we took soundings once, and a second time in the dog-watch, in 60 fathom, clean, grey sand. In the second glass of the day-watch we got a breeze from the south-east, upon which we tacked for the shore again.

Item the 17th.

In the morning at sunrise we were about one mile from the shore; in various places we saw smoke ascending from fires made by the natives; the wind then being south and blowing from the land we again tacked to eastward. At noon Latitude estimated 40° 31', Longitude 190° 47'; course kept north-east by east, sailed 12 miles; in the afternoon the wind being west we held our course east by south along a low-lying shore with dunes in good dry weather; we sounded in 30 fathom, black sand, so that by night one had better approach this land aforesaid, sounding; we then made for this sandy point until we got in 17 fathom, where we cast anchor at sunset owing to a calm, when we had the northern extremity of this dry sandspit west by north of us; also high land extending to east by south; the point of the reef south-east of us; here inside this point or narrow sandspit we saw a large open bay upward of 3 or 4 miles wide; to eastward of this narrow sandspit there is a sandbank upwards of a mile in length with 6, 7, 8 and 9 feet of water above it, and projecting east-south-east from the said point. In the evening we had 9° North-East variation.

Item the 18th.

In the morning we weighed anchor in calm weather; at noon Latitude estimated 40° 49', Longitude 191° 41'; course kept east-south-east, sailed 11 miles. In the morning before weighing anchor, we had resolved with the Officers of the Zeehaan that we should try to get ashore here and find a good harbour; and that as we neared it we should send out the pinnace to reconnoitre; all which may in extenso be seen from this day's resolution. In the afternoon our skipper Ide Tiercxz and our pilot-major Francoys Jacobsz, in the pinnace, and Supercargo Gilsemans, with one of the second mates of the Zeehaan in the latter's cock-boat, went on before to seek a fitting anchorage and a good watering-place. At sunset when it fell a calm we dropped anchor in 15 fathom, good anchoring-ground in the evening, about an hour after sunset, we saw a number of lights on shore and four boats close inshore, two of which came towards us, upon which our own two boats returned on board; they reported that they had found no less than 13 fathom water and that, when the sun sank behind the high land, they were still about half a mile from shore. When our men had been on board for the space of about one glass the men in the two prows began to call out to us in the rough, hollow voice, but we could not understand a word of what they said. We however called out to them in answer, upon which they repeated their cries several times, but came no nearer than a stone shot; they also blew several times on an instrument of which the sound was like that of a Moorish trumpet; we then ordered one of our sailors (who had some knowledge of trumpet-blowing) to play them some tunes in answer. Those on board the Zeehaan ordered their second mate (who had come out to India as a trumpeter and had in the Mauritius been appointed second mate by the council of that fortress and the ships) to do the same; after this had been repeated several times on both sides, and as it was getting more and more dark, those in the native prows at last ceased and paddled off. For more security and to be on guard against all accidents we ordered our men to keep double watches as we are wont to do when out at sea, and to keep in readiness all necessaries of war, such as muskets, pikes and cutlasses. We cleaned the guns on the upper-orlop, and placed them again, in order to prevent surprises, and be able to defend ourselves if these people should happen to attempt anything against us. Variation 9° North-East.

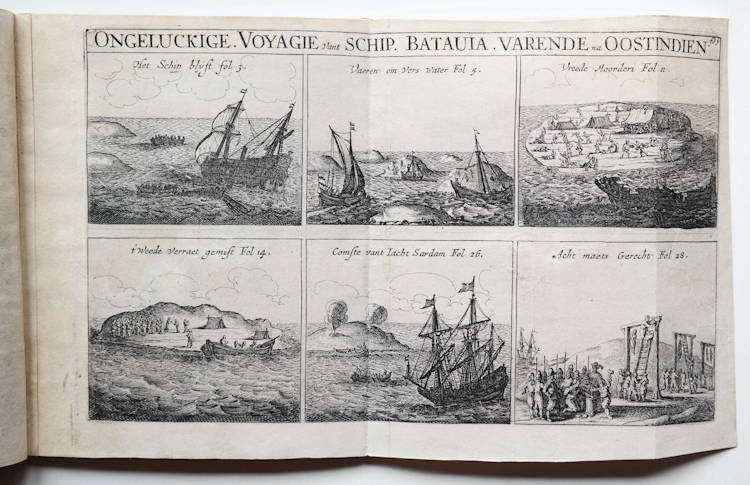

Item the 19th.

Early in the morning a boat manned with 13 natives approached to about a stone's cast from our ships; they called out several times but we did not understand them, their speech not bearing any resemblance to the vocabulary given us by the Honourable Governor-General and Councillors of India, which is hardly to be wondered at, seeing that it contains the language of the Salomonis islands, etc. As far as we could observe these people were of ordinary height; they had rough voices and strong bones, the colour of their skin being brown and yellow; they wore tufts of black hair right upon the top of their heads, tied fast in the manner of the Japanese at the back of their heads, but somewhat longer and thicker, and surmounted by a large, thick white feather. Their boats consisted of two long narrow prows side by side, over which a number of planks or other seats were placed in such a way that those above can look through the water underneath the vessel: their paddles are upwards of a fathom in length, narrow and pointed at the end; with these vessels they could make considerable speed. For clothing, as it seemed to us, some of them wore mats, others cotton stuffs; almost all of them were naked from the shoulders to the waist. We repeatedly made signs for them to come on board of us, showing them white linen and some knives that formed part of our cargo. They did not come nearer, however, but at last paddled back to shore. In the meanwhile, at our summons sent the previous evening, the officers of the Zeehaan came on board of us, upon which we convened a council and resolved to go as near the shore as we could, since there was good anchoring-ground here, and these people apparently sought our friendship. Shortly after we had drawn up this resolution we saw 7 more boats put off from the shore, one of which (high and pointed in front, manned with 17 natives) paddled round behind the Zeehaan while another, with 13 able-bodied men in her, approached to within half a stone's throw of our ship; the men in these two boats now and then called out to each other; we held up and showed them as before white linens, etc., but they remained where they were. The skipper of the Zeehaan now sent out to them his quartermaster with her cock-boat with six paddlers in it, with orders for the second mates that, if these people should offer to come alongside the Zeehaan, they should not allow too many of them on board of her, but use great caution and be well on their guard. While the cock-boat of the Zeehaan was paddling on its way to her those in the prow nearest to us called out to those who were lying behind the Zeehaan and waved their paddles to them, but we could not make out what they meant. Just as the cock-boat of the Zeehaan had put off from board again those in the prow before us, between the two ships, began to paddle so furiously towards it that, when they were about halfway slightly nearer to our ship, they struck the Zeehaan's cock-boat so violently alongside with the stem of their prow that it got a violent lurch, upon which the foremost man in this prow of villains with a long, blunt pike thrust the quartermaster Cornelis Joppen in the neck several times with so much force that the poor man fell overboard. Upon this the other natives, with short thick clubs which we at first mistook for heavy blunt parangs, and with their paddles, fell upon the men in the cock-boat and overcame them by main force, in which fray three of our men were killed and a fourth got mortally wounded through the heavy blows. The quartermaster and two sailors swam to our ship, whence we had sent our pinnace to pick them up, which they got into alive. After this outrageous and detestable crime the murderers sent the cock-boat adrift, having taken one of the dead bodies into their prow and thrown another into the sea.

Ourselves and those on board the Zeehaan seeing this, diligently fired our muskets and guns and, although we did not hit any of them, the two prows made haste to the shore, where they were out of the reach of shot. With our fore upper-deck and bow guns we now fired several shots in the direction of their prows, but none of them took effect. There upon our skipper Ide Tercxsen Holman, in command of our pinnace well manned and armed, rowed towards the cock-boat of the Zeehaan (which fortunately for us these accursed villains had let adrift) and forthwith returned with it to our ships, having found in it one of the men killed and one mortally wounded. We now weighed anchor and set sail, since we could not hope to enter into any friendly relations with these people, or to be able to get water or refreshments here. Having weighed anchor and being under sail, we saw 22 prows near the shore, of which eleven, swarming with people, were making for our ships. We kept quiet until some of the foremost were within reach of our guns, and then fired 1 or 2 shots from the gun-room with our pieces, without however doing them any harm; those on board the Zeehaan also fired, and in the largest prow hit a man who held a small white flag in his hand, and who fell down. We also heard the canister-shot strike the prows inside and outside, but could not make out what other damage it had done. As soon as they had got this volley they paddled back to shore with great speed, two of them hoisting a sort of tingang sails. They remained lying near the shore without visiting us any further. About noon skipper Gerrit Jansz and Mr. Gilsemans again came on board of us; we also sent for their first mate and convened the council, with whom we drew up the resolution following, to wit: Seeing that the detestable deed of these natives against four men of the Zeehaan's crew, perpetrated this morning, must teach us to consider the inhabitants of this country as enemies; that therefore it will be best to sail eastward along the coast, following the trend of the land in order to ascertain whether there are any fitting places where refreshments and water would be obtainable; all of which will be found set forth in extenso in this day's resolution. In this murderous spot (to which we have accordingly given the name of Moordenaersbay[ Murderer's Bay]) we lay at anchor on 40° 50' South Latitude, 191° 30' Longitude. From here we shaped our course east-north-east. At noon Latitude estimated 40° 57', Longitude 191° 41'; course kept south, sailed 2 miles. In the afternoon we got the wind from the west-north-west when, on the advice of our steersmen and with our own approval, we turned our course north-east by north. During the night we kept sailing as the weather was favourable, but about an hour after midnight we sounded in 25 or 26 fathom, a hard, sandy bottom. Soon after the wind went round to north-west, and we sounded in 15 fathom; we forthwith tacked to await the day, turning our course to westward, exactly contrary to the direction by which we had entered. Variation 9° 30' North-East.

This is the second land which we have sailed along and discovered. In honour of their High Mightinesses the States-General we gave Staten Landt, since we deemed it quite possible that this land is part of the great Staten Land, though this is not certain. This land seems to be a very fine country and we trust that this is the mainland coast of the unknown South land. To this course we have given the name of Abel Tasman passagie, because he has been the first to navigate it.

[The five pages following are taken up by coast-surveyings and drawings with inscriptions]

Item the 20th.

In the morning we saw land lying here on all sides of us, so that we must have sailed at least 30 miles into a bay. We had at first thought that the land off which we had anchored was an island, nothing doubting that we should here find a passage to the open South Sea; but to our grievous disappointment it proved quite otherwise. The wind now being westerly we henceforth did our best by tacking to get out at the same passage through which we had come in. At noon Latitude observed 40° 51' South, Longitude 192° 55'; course kept east half a point northerly, sailed 14 miles. In the afternoon it fell calm. The sea ran very strong into this bay so that we would make no headway but drifted back into it with the tide. At noon we tacked to northward when we saw a round high islet west by south of us, at about 8 miles distance which we had passed the day before; the said island lying about 6 miles east of the place where we had been at anchor and in the same latitude. This bay into which we had sailed so far by mistake showed us everywhere a fine good land: near the shore the land was mainly low and barren, the inland being moderately high. As you are approaching the land you have everywhere an anchoring-ground gradually rising from 50 or 60 fathom to 15 fathom when you are still fully 1½ or 2 miles from shore. At three o'clock in the afternoon we got a light breeze from the south-east but as the sea was very rough we made little or no progress. During the night we drifted in a calm; in the second watch, the wind being westerly, we tacked to northward.

Item the 21st.

During the night in the dog-watch we had a westerly wind with a strong breeze; we steered to the north, hoping that the land which we had had north-west of us the day before might fall away to northward, but after the cook had dished we again ran against it and found that it still extended to the north-west. We now tacked, turning from the land again and, as it began to blow fresh, we ran south-west over towards the south shore. At noon, Latitude observed 40° 31', Longitude 192° 55'; course kept north, sailed 5 miles. The weather was hazy so that we could not see land. Halfway through the afternoon we again saw the south coast; the island which the day before we had west of us at about 6 miles distance now lay south-west by south of us at about 4 miles distance. We made for it, running on until the said island was north-north-west of us, then dropped our anchor behind a number of cliffs in 33 fathom, sandy ground mixed with shells. There are many islands and cliffs all round here. We struck our sail-yards for it was blowing a storm from the north-west and west-north-west.

Item the 22nd.

The wind north-west by north and blowing so hard that there was no question of going under sail in order to make any progress; we found it difficult enough for the anchor to hold. We therefore set to refitting our ship. We are lying here in 40° 50' South Latitude and Longitude 192° 37'; course held south-west by south, sailed 6 miles. During the night we got the wind so hard from the north-west that we had to strike our tops and drop another anchor. The Zeehaan was almost forced from her anchor and therefore hove out another anchor likewise.

Item the 23rd.

The weather still dark, hazy and drizzling; the wind north-west and west-north-west with a storm so that to our great regret we could not make any headway.

Item the 24th.

Still rough, unsteady weather, the wind still north-west and stormy; in the morning when there was a short calm we hoisted the white flag and got the officers of the Zeehaan on board of us. We then represented to them that since the tide was running from the south-east there was likely to be a passage through, so that perhaps it would be best, as soon as wind and weather should permit, to investigate this point and see whether we could get fresh water there; all of which may in extenso be seen from the resolution drawn up concerning this matter.

Item the 25th.

In the morning we reset our tops and sailyards, but out at sea things looked still so gloomy that we did not venture to weigh our anchor. Towards evening it fell a calm so that we took in part of our cable.

Item the 26th.

In the morning, two hours before day, we got the wind east-north-east with a light breeze. We weighed anchor and set sail, steered our course to northward, intending to sail northward round this land; at daybreak it began to drizzle, the wind went round to the south-east, and afterwards to the south as far as the south-west, with a stiff breeze. We had soundings in 60 fathom, and set our course by the wind to westward. At noon Latitude estimated 40° 13', Longitude 192° 7'; course kept north-north-west, sailed 20 miles. Variation 8° 40'. During the night we lay to with small sail.

Item the 27th.

In the morning at daybreak we made sail again, set our course to northward, the wind being south-west with a steady breeze; at noon Latitude observed 38° 38', Longitude 190° 15'; course kept north-west, sailed 26 miles. At noon we shaped our course north-east. During the night we lay to under small sail. Variation 8° 20'.

Item the 28th.

In the morning at daybreak we made sail again, set our course to eastward in order to ascertain whether the land we had previously seen in 40° extends still further northward, or whether it falls away to eastward. At noon we saw east by north of us a high mountain which we at first took to be an island; but afterwards we observed that it forms part of the mainland. We were then about 5 miles from shore and took soundings in 50 fathom, fine sand mixed with clay. This high mountain is in 38° South Latitude. So far as I could observe this coast extends south and north. It fell a calm, but when there came a light breeze from the north-north-east we tacked to the north-west. At noon Latitude estimated 38° 2', Longitude 192° 23'; course held north-east by east, sailed 16 miles. Towards the evening the wind went round to north-east and north-east by east, stiffening more and more, so that at the end of the first watch we had to take in our topsails. Variation 8° 30'.

Item the 29th.

In the morning at daybreak we took in our bonnets and had to lower our foresail down to the stem. At noon Latitude estimated 37° 17', Longitude 191° 26'; towards noon we again set our foresail and then tacked to westward, course kept north-west, sailed 16 miles.

Item the 30th.

In the morning, the weather having somewhat improved, we set our topsails and slid out our bonnets. We had the Zeehaan to lee of us, tacked and made towards her. We then had the wind west-north-west with a top-gallant gale. At noon Latitude observed 37°, Longitude 191° 55'; course held north-east, sailed 7 miles. Towards evening we again saw the land bearing from us north-east and north-north-east, on which account we steered north and north-east. Variation 8° 40' North-East.

[The next page has two coast-surveyings, with inscriptions]

Item the last.

At noon we tacked about to northward, the wind being west-north-west with a light breeze. At noon Latitude observed 36° 45', Longitude 191° 46'; course kept north-west, sailed 7 miles. In the evening we were about 3 miles from shore; at the expiration of 4 glasses in the first watch we again tacked to the north; during the night we threw the lead in 80 fathom. This coast here extends south-east and north-west; the land is high in some places and covered with dunes in others. Variation 8°.

[January 1643]

Item the 1st of January.

In the morning we drifted in a calm along the coast which here still stretches north-west and south-east. The coast here is level and even, without reefs or shoals. At noon we were in Latitude 36° 12', Longitude 191° 7'; course kept north-west, sailed 10 miles. About noon the wind came from the south-south-east and south-east; we now shaped our course west-north-west in order to keep off shore since there was a heavy surf running. Variation 8° 30' North-East.

Item the 2nd.

Calm weather. Halfway through the afternoon we got a breeze from the east; we directed our course to the north-north-west; at the end of the first watch, however, we turned our course to the north-west so as not to come too near the shore and prevent accidents, seeing that in the evening we had the land north-north-west of us. At noon we were in Latitude 35° 55', Longitude 190° 47'; course kept north-west by west, sailed 7 miles. Variation 9°.

Item the 3rd.

In the morning we saw the land east by north of us at about 6 miles distance and were surprised to find ourselves so far from shore. At noon Latitude observed 35° 20', Longitude 190° 17', course held north-west by north, sailed 11 miles. At noon the wind went round to the south-south-east, upon which we steered our course east-north-east to get near the shore again. In the evening we saw land north and east-south-east of us.

Item the 4th.

In the morning we found ourselves near a cape, and had an island north-west by north of us, upon which we hoisted the white flag for the Officers of the Zeehaan to come on board of us, with whom we resolved to touch at the island aforesaid to see if we could there get fresh water, vegetables, etc. At noon Latitude observed 34° 35', Longitude 191° 9'; course kept north-east, sailed 15 miles, with the wind south-east. Towards noon we drifted in a calm and found ourselves in the midst of a very heavy current which drove us to the westward. There was besides a heavy sea running from the north-east here, which gave us great hopes of finding a passage here. This cape which we had east-north-east of us is in 34° 30' South Latitude. The land here falls away to eastward. In the evening we sent to the Zeehaan the pilot-major with the secretary, as we were close to this island and, so far as we could see, were afraid there would be nothing there of what we were in want of; we therefore asked the opinion of the officers of the Zeehaan whether it would not be best to run on, if we should get a favourable wind during the night, which the officers of the Zeehaan fully agreed with. Variation 8° 40' North-East.

[The two pages following. contain a double-page chart of New Zealand from Cape Maria Van Diemen as far as the 43rd degree S. Latitude, with inscription]

Item the 5th.

In the morning we still drifted in a calm, but about 9 o'clock we got a slight breeze from the south-east, whereupon with our friends of the Zeehaan we deemed it expedient to steer our course for the island before mentioned. About noon we sent to the said island our pinnace with the pilot-major, together with the cock-boat of the Zeehaan with Supercargo Gilsemans in it, in order to find out whether there was any fresh water to be obtained there. Towards the evening they returned on board and reported that, having come near the land, they had paid close attention to everything and had taken due precautions against sudden surprises or assaults on the part of the natives; that they had entered a safe but small bay, where they had found good fresh water, coming in great plenty from a steep mountain, but that, owing to the heavy surf on the shore, it was highly dangerous, nay well-nigh impossible for us to get water there, that therefore they pulled farther round the said island, trying to find some other more convenient water-place elsewhere, that on the said land they saw in several places on the highest hills from 30 to 35 persons, men of tall stature, so far as they could see from a distance, armed with sticks or clubs, who called out to them in a very loud, rough voice, certain words which our men could not understand; that these persons, in walking on, took enormous steps or strides. As our men were rowing about some few in number now and then showed themselves on the hill-tops, from which our men very credibly concluded that these natives in this way generally keep in readiness their assegais, boats and small arms, after their wonted fashions; so that it may fairly be inferred that few, if any, more persons inhabit the said island than those who showed themselves; for in rowing round the island our men nowhere saw any dwellings or cultivated land except just by the fresh water above referred to, where higher up on both sides the running water they saw everywhere square beds looking green and pleasant, but owing to the great distance they could not discern what kind of vegetables they were. It is quite possible that all these persons had their dwellings near the said fresh water. In the bay aforesaid they also saw two prows hauled on shore, one of them seaworthy, the other broken, but they nowhere saw any other craft. Our men having returned on board with the pinnace, we forthwith did our best to get near the shore, and in the evening we anchored in 40 fathom, good bottom, at a small swivel-gun-shot distance from the coast. We forthwith made preparations for taking in water the next day. The said island is in 34° 25' South Latitude and 190° 40' average Longitude.

Item the 6th.

Early in the morning we sent to the watering-place the two boats, to wit ours and the cock-boat of the Zeehaan, each furnished with two pederaroes, 6 musketeers, and the rowers with pikes and side-arms, together with our pinnace with the pilot-major Francoys Jacobsz and skipper Gerrit Jansz, with casks for getting fresh water. While rowing towards the shore they saw, in various places on the heights, a tall man standing with a long stick like a pike, apparently watching our men. As they were rowing past he had called out to them in a very loud voice; when they had got about halfway to the watering-place, between a certain point and another large high rock or small island, they found the current to run so strongly against the wind that, with the empty boats, they had to do their utmost to hold their own; for which reason the pilot-major and Gerrit Jansz, skipper of the Zeehaan, agreed together to abstain from exposing the small craft and the men to such great peril, seeing that there was still a long voyage before them and the men and the small craft were greatly wanted by the ships. They therefore pulled back to the ships, the rather as a heavy surf was rolling on the shore near the watering-place. The breeze freshening, we could easily surmise that they had not been able to land, and now made a sign to them from our ship with the furled flag, and fired a gun to let them know that they were at liberty to return, but they were already on their way back before we signalled to them. The pilot-major, having come alongside our ship again with the boats, reported that owing to the wind the attempt to land there was too dangerous, seeing that the sea was everywhere near the shore full of hard rocks without any sandy ground, so that they would have greatly imperilled the men and run the risk of having the water-casks injured or stove in; we forthwith summoned the officers of the Zeehaan and the second mates on board of us, and convened a council in which it was resolved to weigh anchor directly and to run on an easterly course as far as 220° Longitude, in accordance with the preceding resolution; then to shape our course to northward, or eventually due north, as far as Latitude 17° South, after which we shall hold our course due west in order to run straight of the Cocos and Hoorense islands, where we shall take in fresh water and refreshments; or if we should meet with any other island before these we shall endeavour to touch at them, in order to ascertain what can be obtained there; all this being duly specified and set forth at length in this day's resolution, to which for briefness sake we beg leave to refer. About noon we set sail; at noon we had the island due south of us at about 3 miles distance; in the evening at sunset it was south-south-west of us at 6 or 7 miles distance, the island and the rocks lying south-west and north-east of each other. During the night it was pretty calm with an east-south-east wind, our course being north-north-east, very close to the wind, while the tide was running in from the north-east.

Item the 7th.

Good weather, the wind blowing from east by south and east-south-east with a topsail breeze; at noon Latitude observed 33° 25', Longitude 191° 9'; course kept north-east, sailed 16 miles. The sea is running very high from the eastward, so that in the direction there is not likely to be any mainland. Variation 8° 30'.

J.E. Heeres' translation.

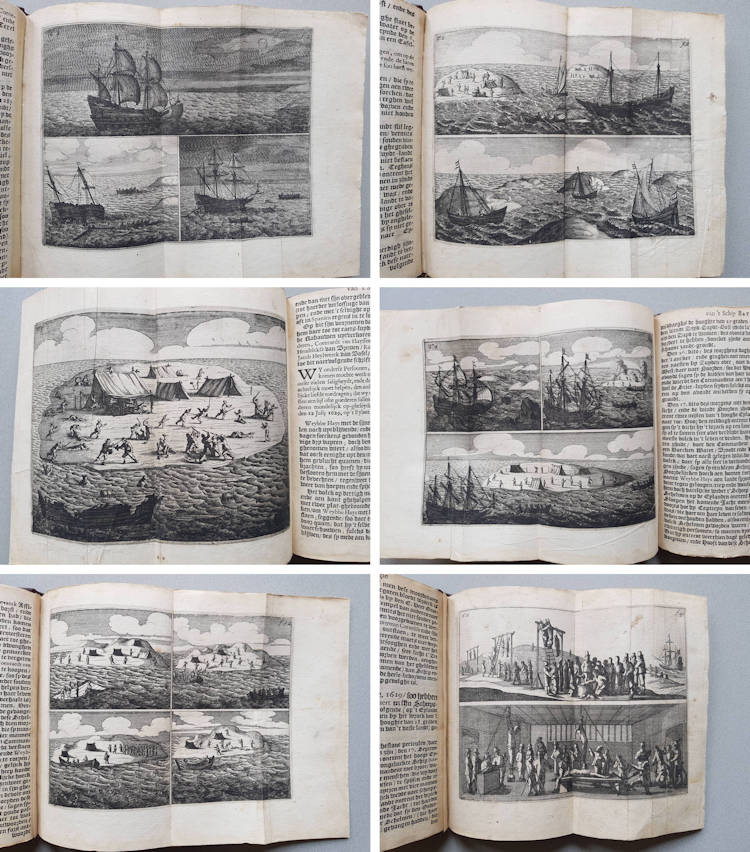

François Valentijn (1666 – 1727)

François Valentijn (17 April 1666 – 1727) was a Dutch minister, naturalist and author whose Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën ("Old and New East-Indies") describes the history of the Dutch East India Company and the countries of the Far East.

François Valentijn was born in 1666 in Dordrecht, as the eldest of seven children of Abraham Valentijn and Maria Rijsbergen. He lived most of his life in Dordrecht; however, he is known for his activities in the tropics, notably in Ambon, in the Maluku Archipelago. Valentijn studied theology and philosophy at the University of Leiden and the University of Utrecht before leaving for a career as a preacher in the Indies.

In total, Valentijn lived in the East Indies for 16 years. Valentijn was first employed by the VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) at the age of 19 as minister to the East Indies, where he became a friend of the German naturalist Georg Eberhard Rumpf (Rumphius). He returned and lived in the Netherlands for about ten years before returning to the Indies in 1705 where he was to serve as army chaplain on an expedition in eastern Java.

He finally returned to Dordrecht where he found time to write his Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (1724–26) a massive work of five parts published in eight volumes and containing over one thousand engraved illustrations and some of the most accurate maps of the Indies of the time. He died in The Hague, Netherlands, in 1727.

Valentijn probably had access to the VOC's archive of maps and geographic trade secrets, which they had always guarded jealously. Johannes van Keulen II (d. 1755) became Hydrographer to the V.O.C. at the time Valentijn's Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën was published. It was in the younger van Keulen's time that many of the VOC charts were first published, one signal of the decline of Dutch dominance in the spice trade. One uncommon grace afforded Valentijn was that he lived to see his work published; the VOC (Dutch East India Company) strictly enforced a policy prohibiting former employees from publishing anything about the region or their colonial administration.

(Wikipedia)

"The first book to give a comprehensive account, in text and illustration, of the peoples, places and natural history of Indonesia."

(Bastin & Brommer)

The Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien was created both from the voluminous journals Valentijn had amassed during his two stays in Southeast Asia, as well as from his own research, correspondence, and from previously unpublished material secured from VOC officials. The work contained an unprecedented selection of large-scale maps and views of the Indies, many of which were superior to previously available maps.

(Suarez)

François Valentijn's Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien (Old and New East Indies) has for long been regarded as a primary source of information on a number of regions of maritime Asia. It is a veritable encyclopaedia, bringing together an array of facts, trivial and vital, from a wide range of contemporary and earlier literature, acknowledged and unacknowledged, and contains valuable excerpts from contemporary documents of the Dutch East India Company and from private papers.

(Arasaratnam)

François Valentijn was born on April 17, 1666, in the city of Dordrecht, the Netherlands, as the eldest of seven children of Abraham Valentijn and Maria Rijsbergen. He studied theology at the universities of Utrecht and Leiden. During his life he spent nearly fifteen years as a minister in the Dutch East-Indies (1685–1694 and 1706–1713), mostly in the Moluccan Archipelago. In 1692 he entered into matrimony with Cornelia Snaats (1660–1717) who bore him two daughters. Valentijn died on August 6, 1727, in the city of The Hague. Valentijn is often noted for his role in discussions about early translations of the Bible into Malay. However, his established reputation rests on his multivolume work on Asia titled Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indië (Old and New East-Indies).

REVEREND VALENTIJN IN THE MOLUCCAS

At the age of nineteen, Valentijn was called to the ministry on Ambon Island, the chief trade and administrative hub of the Moluccan Archipelago. In the city of Ambon, he preached in the Malay language and trained local Ambonese assistant ministers, while also having to inspect some fifty Christian parishes in the region.

In the 1600s the catechism and liturgy were offered in so-called High-Malay, which most local Christians did not understand. Valentijn fervently opposed the use of High-Malay and instead propagated Ambon-Malay because, in his opinion, all Christian communities in the Indies understood this local dialect.

During his stay in Ambon, a number of Valentijn's colleagues blamed him for paying too much attention to his wife and making a living from usury. On top of these accusations, he was found guilty of manipulating official church records. The relationship with his colleagues grew tense because Valentijn disliked his task of inspecting the Christian parishes on other islands. In 1694 he returned to the Netherlands where he spent much time on his Bible translation.

In 1705 Valentijn returned to Ambon. During this period, Reverend Valentijn got into a conflict with the governor of Ambon about too much interference of the secular administration in church affairs without the consent of the church administration. This conflict worsened after Valentijn rejected his call by the central colonial administration to the island of Ternate. In 1713 his repeated request for repatriation was finally met.

THE MALAY BIBLE TRANSLATION

In 1693 during a meeting with the Church Council of Batavia, Valentijn announced that he had completed the translation of the Bible into Ambon-Malay. The Church Council refused to publish Valentijn's translation because two years earlier they assigned the task of translating the Bible into High-Malay to the Batavia-based Reverend Melchior Leydecker.

After Valentijn returned to the Netherlands in 1695, he rallied support for his translation. A heated discussion unfolded, in which Valentijn and, amongst others, the Dutch Reformed synods of both the provinces of North- and South-Holland, opposed the critique of Leydecker and the Church Council of Batavia. The Council's criticism largely concerned Valentijn's use of a poor dialect of Malay. The synods in the Netherlands were not in the position to participate in the debate as most relevant linguists resided in the Indies, but Valentijn's personal network most likely contributed to the support for Valentijn's translation.

In 1706 a special commission of ministers in the Indies inspected a revised edition of Valentijn's translation but still noticed a number of shortcomings. Although Valentijn told the commission that he would redo the translation, the final revised edition was never presented to the Church Council. The Council eventually decided to publish Leydecker's High-Malay translation, which was used in the Moluccas from 1733 onward into the twentieth century.

OUD EN NIEUW OOST-INDIË

From 1719 onward, Valentijn, as a private citizen, devoted himself chiefly to his magnum opus, Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indië (ONOI), comprising his own notes, observations, sections of writings from his personal library, and materials trusted to him by former colonial officials. In 1724, the first two volumes were published in the cities of Dordrecht and Amsterdam, followed by the following three volumes in 1726. This work comprises geographical and ethnological descriptions of the Moluccas and the trading contacts of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) throughout Asia.

Scholars consider this substantial work the first Dutch encyclopedic reference for Asia. ONOI contains factual data, descriptions of persons and towns, anecdotes, ethnological engravings, maps, sketches of coastlines, and city plans, as well as excerpts of official documents of the church council and colonial administration.

Valentijn wrote in an uncorrupted form of Dutch, which many contemporary writers were not able to compete with. The structure of Valentijn's colossal work is rather chaotic: the descriptions of more than thirty regions are erratically spread over a total number of forty-nine books in five volumes, each consisting of two parts, and held together in eight bindings.

Since the publication of ONOI, numerous scholars have accused Valentijn of plagiarism. It is true that he included abstracts of other works, such as the celebrated account on the Ambon islands by Rumphius, without referencing them properly. However, general acknowledgment of sources can be found in several places, for example, in his preface to the third volume.

THE INFLUENCE OF VALENTIJN'S WORK

For almost two centuries, Valentijn's work was the single credible reference for Asia. ONOI was therefore used as the main manual for Dutch civil servants and colonial administrators who were sent to work in the East Indies.

Valentijn's work is still a major source for historical studies on the Dutch East Indies. For example, the reference book on Dutch-Asiatic shipping in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (The Hague, 1979–1987) was compiled on the basis of materials derived from Valentijn's work. The importance of ONOI for the historical reconstruction of other regions is clearly demonstrated by the publication of English translations of Valentijn's parts concerning the Cape of Good Hope (1971–1973) and the first twelve chapters of his description of Ceylon (1978).

Valentijn's work also proved to be of great importance for the natural history of the Moluccas. Valentijn included in ONOI descriptions by Rumphius on, for example, Ambonese animals, while Rumphius's original unpublished manuscript was later lost. In 1754 Valentijn's part on sea flora and fauna was separately published in Amsterdam, and some twenty years later translated into German. It was only in 2004 that the complete ONOI was reprinted and made available to a larger public.

(Encyclopedia.com)

Related Categories

Related Items