Leen Helmink Antique Maps

Antique map of the Holy Land by Fries / Waldseemüller

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 19044

Zoom ImageDescription

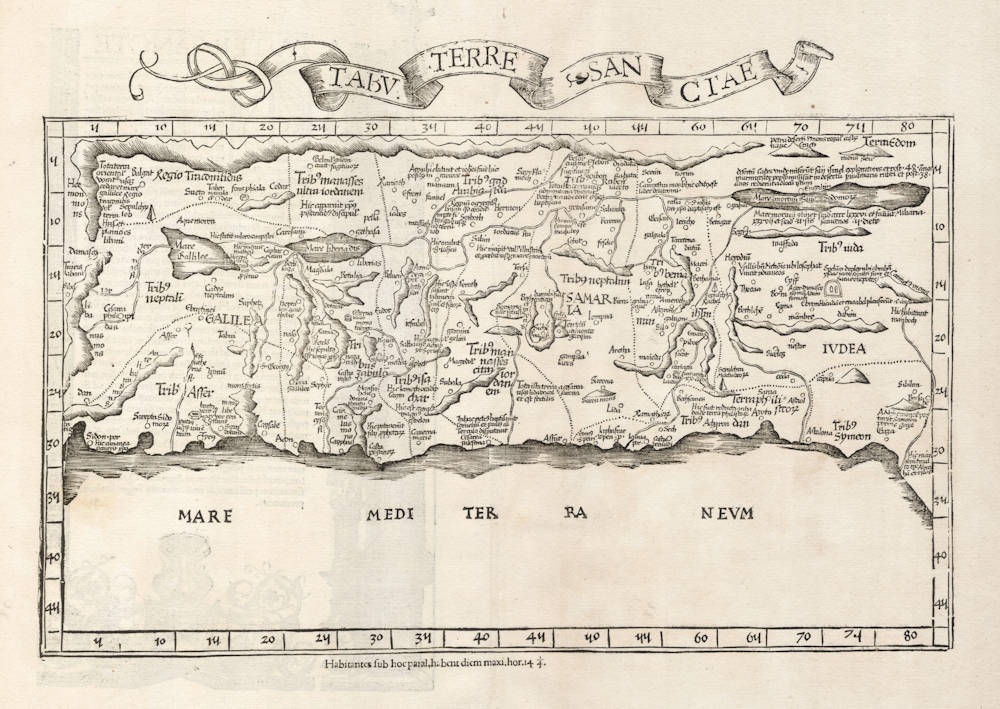

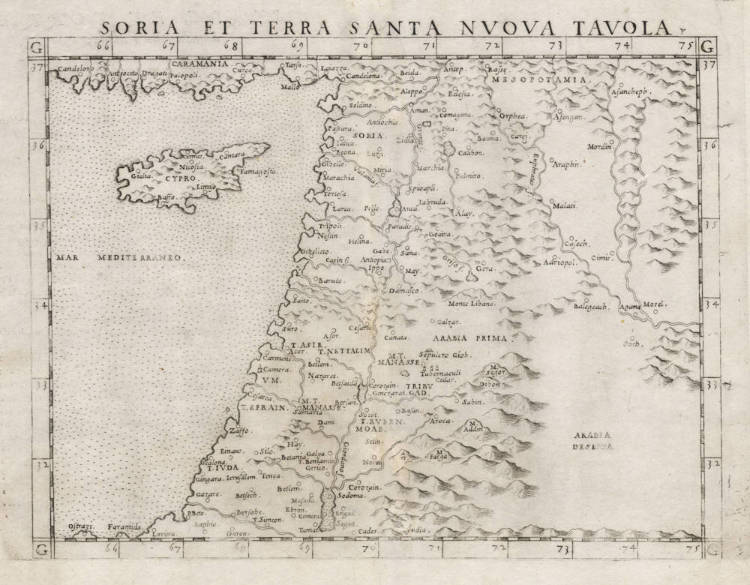

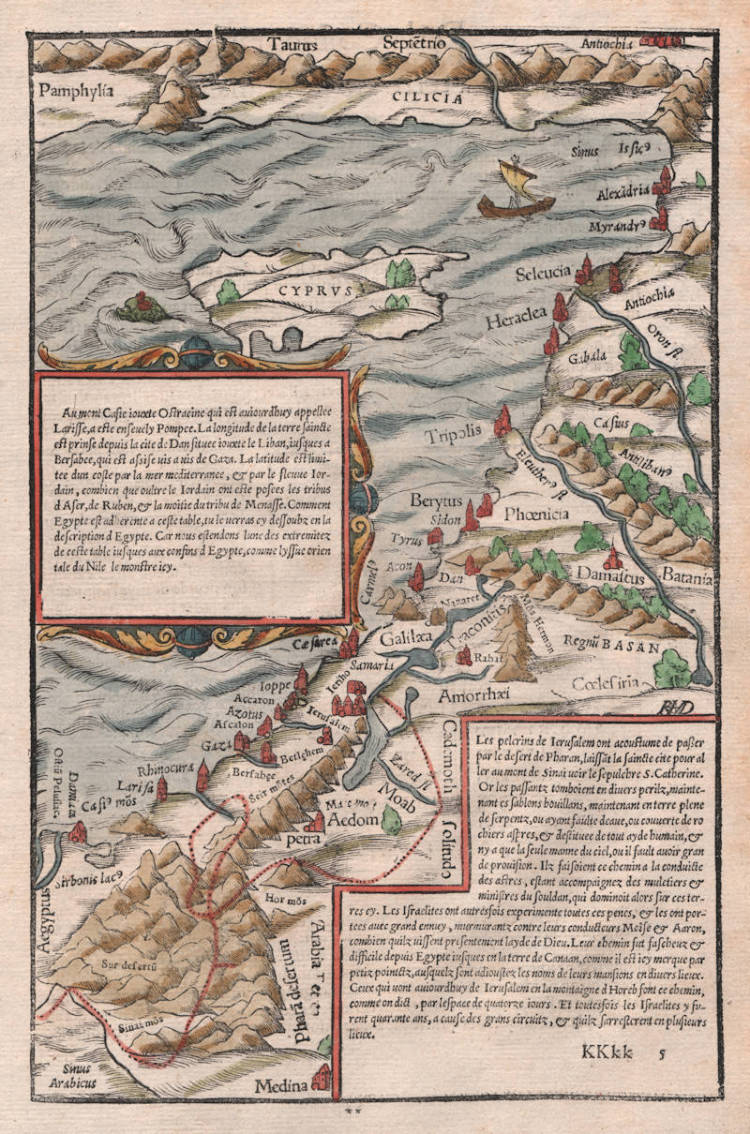

One of the earliest collectible maps of the Holy Land. The map is a reduced version of Waldseemuller's 1513 map, the cartography of which is based on a manuscript map by the crusader Petrus (Pietro) Vesconte, for Marino Sanuto's Liber Secretorum Fidelibus de Crucis (The Book of the Secrets of the Faithful of the Cross) of circa 1320, and updated by Donnus Nicholaus Germanaus in 1482.

Condition

Strong and early imprint of the woodblock. Mint collector's condition.

Maps of the Holy Land: Cartobibliography of printed maps, 1475-1900

Oriented to the East. Modern map of Palestine, the shore line running from Sidon to Gaza and inland showing the whole of Palestine on both sides of the Jordan, divided into 12 Tribes. The Carmel Mountain is drawn like a sturdy tree with two outstretched branches. The lake of Merom is called Mare Galilee and is out of size [oversized], and the Dead Sea is shown as an elongated narrow lake. The Jordan River in its wide meanderings is shown as a thin line. After Vesconte-Sanuto's map of Palestine.

(Laor)

[Ptolemy atlas] Argentorati 1522 Fol.

In the [verso] legend to Tabula moderna terrae Sanctae is the following passage [at the end]:

Scias tamen, lector optime, iniuria aut jactantia pura, tantam huic terrae bonitatum fuisse adscriptam, eo quod ipsa experientia mercatorum et peregre proficiscentium, hanc inclutam, sterilem, omni dulcedine carentem depromit. Quare promissam terram pollicitam et non vernacula lingua laudantem pronuncies.

This phrase was repeated in the edition 1525, without attracting the attention of the religious fanatics of the time. But when they were copied by Michael Servetus, in the edition of 1535, they created a great scandal, and became one of the main charges against this unfortunate sceptic, who was burned through the machinations of Calvin.

(Nordenskiöld)

Lorenz Fries

The later two editions of 1535 and 1541 were edited by Michael Servetus (or Villanovus), a Spanish doctor resident in Lyons. In those difficult times, Servetus was accused of heresy. One piece of evidence used against him was a passage on the reverse of the modern map of the Holy Land, which said that "Palestine was not such a fertile land as was generally believed, since modern travellers reported it barren". Unfortunately, this not Servetus' original view, but was a passage repeated from the 1522 edition.

This charge seems to have counted against Servetus for, when he was burnt at the stake, Calvin ordered that copies of the book should be burnt with him. This has often been cited as a justification to describe examples of the 1535 and 1541 editions as the rarest of the four. However, it should be remembered that Servetus was executed in 1553, twelve years after publication of the final edition, so images of the entire print-run being destroyed are exaggerated. In fact, the 1535 and 1541 editions are the two editions most commonly encountered, both in libraries and on the market, which would suggest the Calvinist authorities may only have burnt a few token copies.

(Ashley Baynton-Williams)

Laurent Fries (c.1490-c.1532)

Laurent Fries (Laurentius Frisius), born in Mulhouse in Burgundy, travelled widely, studying as a physician and mathematician in Vienne, Padua, Montpellier and Colmar before settling in Strassburg. There he is first heard of working as a draughtsman on Peter Apian's highly decorative cordiform World Map, published in 1520. Apian’s map was based on Waldseemüller's map of 1507 which no doubt inspired Fries's interest in the Waldseemüller Ptolemy atlases of 1513 and 1520 and brought him into contact with the publisher, Johannes Grüninger. It is thought that Grüninger had acquired the woodcuts of the 1520 edition with the intention of producing a new version to be edited by Fries. Under his direction the maps were redrawn and although many of them were unchanged, except for size, others were embellished with historical notes and figures, legends and the occasional sea monster. Three new maps were added.

There were four editions of Fries' reduced sized re-issue of Waldseemüller's Ptolemy atlas:

1522 Strassburg: 50 woodcut maps, reduced in size, revised by Laurent Fries (Laurentius Frisius) and included the earliest map showing the name ‘America' which is likely to be available to collectors

1525 Strassburg: re-issue of 1522 maps

1535 Lyon: re-issue of 1522 maps, edited by Michael Servetus who was subsequently tried for heresy and burned at the stake in 1553, ostensibly because of derogatory comments in the atlas about the Holy Land – the fact that the notes in question had not even been written by Servetus, but were copied from earlier editions, left his Calvinist persecutors unmoved

1541 Vienne (Dauphiné): re-issue of the Lyon edition - the offensive comments about the Holy Land have been deleted

(Moreland and Bannister)

Martin Waldseemüller (c.1470-1518)

Waldseemüller, born in Radolfzell, a village on what is now the Swiss shore of Lake Constance, studied for the church at Freiburg and eventually settled in St Dié at the Court of the Duke of Lorraine, at that time a noted patron of the arts. There, in the company of likeminded savants, he devoted himself to a study of cartography and cosmography, the outcome of which was a world map on 12 sheets, now famous as the map on which the name “America’ appears for the first time. Suggested by Waldseemüller in honour of Amerigo Vespucci (latinised: Americus Vesputius) whom he regarded, quite inexplicably, as the discoverer of the New World, the new name became generally accepted by geographers before the error could be rectified, and its use was endorsed by Mercator on his world map printed in 1538. Although only one copy is now known of Waldseemüller's map and of the later Carta Marina (1516) they were extensively copied in various forms by other cartographers of the day.

Waldseemüller is best known for his preparation from about 1507 onwards of the maps for an issue of Ptolemy's Geographia, now regarded as the most important edition of that work. Published by other hands in Strassburg in 1513, it included 20 ‘modern' maps and passed through one other edition in 1520. Four more editions on reduced size were issued of the Laurent Fries version.

It remained the most authoritative work of its time until the issue of Münster's Geographia in 1940 and Cosmographia in 1544.

(Moreland and Bannister)