Leen Helmink Antique Maps

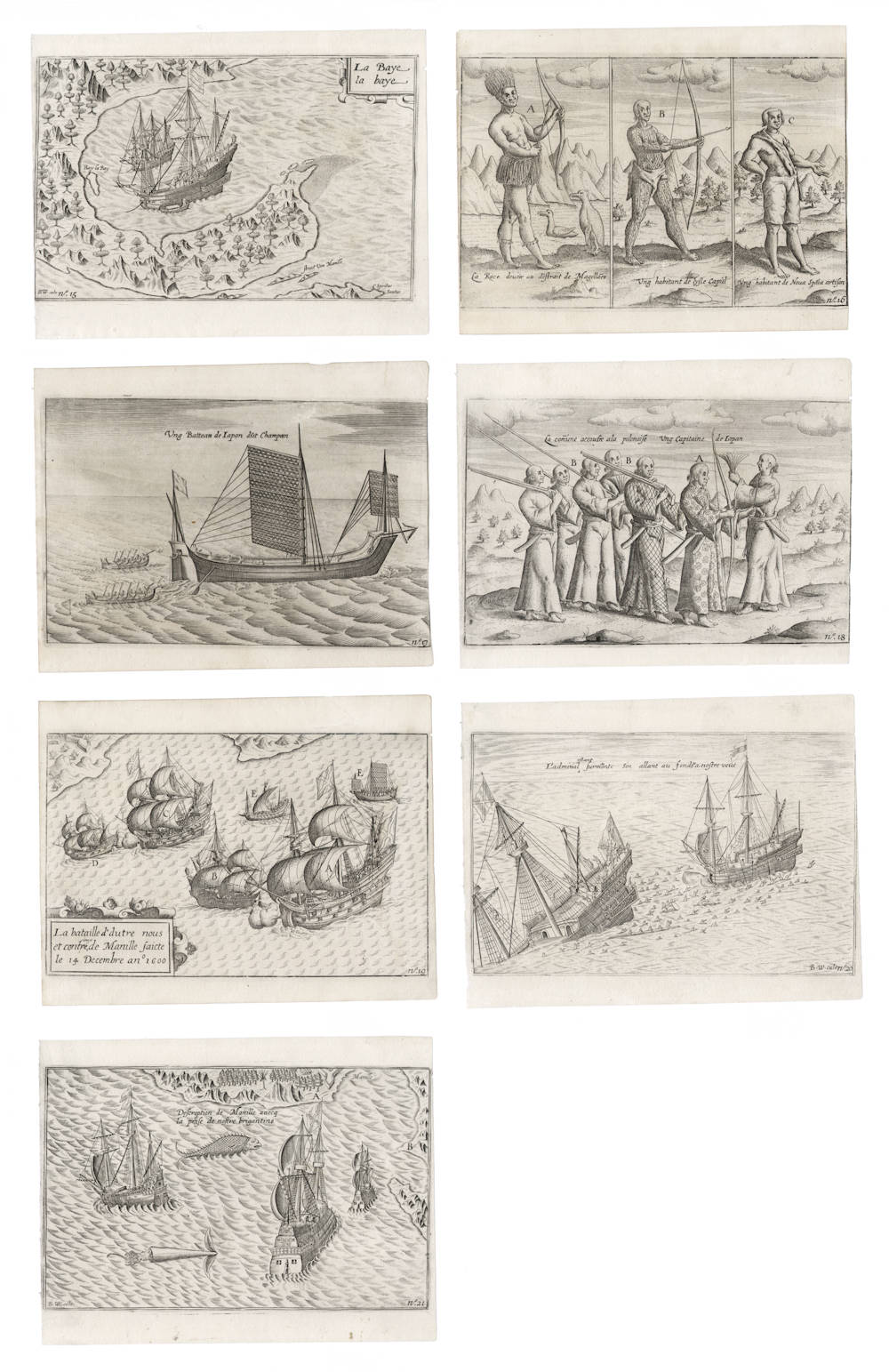

Antique map of the Philippines - 7 maps/views by van Noort

The item below has been sold, but if you enter your email address we will notify you in case we have another example that is not yet listed or as soon as we receive another example.

Stock number: 18900

Zoom ImageCartographer(s)

Olivier van Noort (biography)

Title

Description de Manille avecq la prise de nostre brigantine, La bataille d'autre nous et contre cieux de Manille faicte le 14 Decembre anno 1600

First Published

Amsterdam, 1602

Size

each ca 15 x 23 cms

Technique

Condition

excellent

Price

This Item is Sold

Description

Complete set of all seven maps and views of the Philippines visit of Olivier van Noort. First published in his 1602 printed journal about his circumnavigation of 1598-1601.

These prints are the first printed views of the Philippines and its people. The series also contains the first print of Japanese people, with whom Van Noort traded outside Manila Bay.

Van Noort spent two full months in the Philippines, from October 14th to December 14th, 1600. The series gives a vivid account of his adventures there and the dramatic naval battle with the Spaniards outside Manilla Bay.

These views/maps were first published by Cornelis Claesz in Amsterdam in 1602, to accompany Olivier van Noort's account of his three year circumnavigation of 1598-1601). They were engraved by two of the foremost engravers of the day, Baptista van Doetecum and Benjamin Wright. Here the imprints are in final state, with numbers added in the lower corners, from Isaak Commelin's 1646 "Begin ende Voortgangh van de [VOC]".

The imprints of the copperplates are strong and even. The left and right margins are short, as often. Overall condition is excellent.

The maps/views are listed and described below in chronological order of Van Noort's journal.

1. Map of Albay Bay

Title: La Baye la baye

Coming from the Mariana Islands, on the 14th of October, Van Noort's two remaining ships arrive in Albay Gulf/Bay, off today's Legazpi City. North is at the top of this bird's eye view. Mayon Volcano is in the upper left. Not knowing where they are, they were guessing they were at Cape of Espiritu Santus (the Northeastern point of Samar Island). To avoid trouble with the suspicious Spanish, Van Noort hoists a Spanish flag, dresses up a sailor as a friar, and pretends to be a French ship sailing for the King of Spain. On October 16th, the Spanish commander of Albay finally comes on board and tells them where they are and how exactly to get to Manila. The Spanish commander also orders the Indians to sell the ships fresh supplies of fruits, rice, chicken and pigs.

The print shows the flagship Mauritius and the yacht Eendracht at anchor in the bay on October 16th 1600, two days after their arrival. A spanish sloop is on its port side. The Spanish commander is seen on deck, kissing the hand of the sailor who has been dressed up as a friar. C Spiritus Santus is in the lower left. Straet van Manille (Manila Strait) (today's San Bernadino Strait) is to the northwest of it. The print is signed by master engraver Benjamin Wright (B.W. caela[vit]), who worked for Cornelis Claeszoon in Amsterdam, the leading book and map publisher of the day.

Because the Spanish discovered on Oct 18 that he was not from France but from the rebellious Netherlands, which was at war with the Spanish Empire, he quickly had to weigh anchor and leave Albay Bay at dawn of Oct 20th, after exchange of hostages. With his cover blown and the Spanish aware of his presence in their waters, Van Noort's voyage and his ships in the Philippines were "as safe as a man smoking his pipe in a powder-magazine". The news would quickly reach Manila overland to prepare a war fleet to destroy these Dutch "pirates".

Meanwhile, Van Noort took his time to sail to Manila, his plan was to do profitable business outside Manila Bay with Chinese and Japanese trade ships bound for Manila. His fleet had been financed by private investors, and he had to come back to the Netherlands with a profit to keep them happy. He did not seem too concerned about the Spanish threat, and took his leasure to get to Manila.

"En route to Manila, van Noort put into Albay Bay, in the southeast corner of southern Luzon. The view-map of Albay shows Van Noort's ships anchored in the bay, with the northern tip of Samar in the lower right. The mountains rising in the upper left lead to Mayon Volcano, which soon became an important landmark for sailors, as its near-perfect symmetry and the halo of vapor which often glows at its summit at night, were unmistakable and could be seen from a great distance."

(Suárez on the reduced copy of this print by Theodor de Bry)

"On the seventeenth [September 1600], they set sayle for the Philippinas. On the twentieth, they had Ice [this is an unfortunate translation mistake by Purchas, the original Dutch account by Van Noort reads: 'rain and severe cold'], being then in three degrees. Sixe weekes together they dranke only raine water. On the fourteenth of October, they espied land, and thought, but falsly, that it had beene the Cape of the Holy Ghost [Cape Espiritu Santo, the northeastern point of Samar Island]. On the sixteenth day [of October], there came a Balsy or Canoa, and in the same a Spaniard, which fearing to come aboord, they [the Dutch] displayed a Spanish flagge, and attired one like a Friar to allure him. Which taking effect, the Generall [Van Noort] saluted him, and told him they were Frenchmen, with the [Spanish] Kings commission bound for Manilla, but wanting necessaries, and not knowing where they now were, having lost their Pilot. The Spaniard answered, this place was called Bay la Bay, seven or eight miles to the North, from the straight of Manilla. The Land was fertile, and hee commanded the Indians to bring Rice, Hogges, and Hennes: which was presently effected, and sold for readie money. His name was Henry Nuñes. The next day Francisio Rodrigo, the [local] Governour came to the Ship and did likewise. The Indians go most naked, their skinnes drawne out with indelible lines and figures. They pay for their heads to the Spaniard, tenne single Ryalls for every one above twentie yeeres old. There are few Spaniards, and but one Priest which is of great esteeme: and had they Priests enough, all the neighbour Nations would bee subject to the Spaniard.

Being furnished with necessarie provision, and now also discovered, they departed [from Albay Bay] for the Straight of Manilla [San Bernadino Strait], and were in no small danger of a Rocke [=Reef] the same night. This whole Tract is wast, barren, and full of Rockes. A storme of wind had almost robbed them the next day of their Masts and Sayles, which with such sudden violence assayled them from the South-East, that in their stormie and tedious voyage, they had not encountered a more terrible."

(Purchas 1625 brief english summary version of Van Noort's Journal)

"As the Dutch had heard from the Spanish pilot of three ships of war from Lima that were looking after them, they made sail for the Philippines, with the intention of touching at the Ladrones, and seeking the island of Buena Vista or Guam in thirteen degrees north latitude. On the 30th of June of the same year, 1600, the admiral and council of war resolved to have the Spanish pilot [which they had captured in Chile] thrown into the sea, because, although he ate in the admiral's cabin and was very civilly treated, he had gone as far as to say, in the presence of some of the crew, that he had been poisoned; a malignant imagination, which he had conceived because he had found himself ill [even though all crew had bowel problems]. He even had the impudence to maintain this imposition in presence of all the officers [at his official ship's trial]. Besides this, he had not only sought to escape himself, but had solicited the negroes and ship-boys to do the same.

On the 15th August the prize Buen Jesus was abandoned, as it was very leaky.

On the 14th October they sighted land of the Philippines, which they believed to be the Cape of Espiritu Santo: on the 16th, while they were at anchor off the coast, a canoe came off with a Spaniard on board; he did not venture to come very near, so the Dutch hoisted Spanish colours and dressed up a sailor as a monk, when he took courage and came on board, where the admiral received him well, and told him that they were French who had a commission from the King of Spain to go to Manila, but that the length of the voyage had put them in want of refreshments; he also said that their pilot was dead, and that was why they had entered that bay without knowing where they were.

The Spaniard, whose name was Enrique Nuñez, told them they were in a bay called La Bahia, seven or eight leagues to the north of the Straits of Manila; and he ordered the Indians to fetch them rice, fowls and pigs, which they did, but would only take money in payment. On the 17th October another Spaniard came with a halbard; he was named Francisco Rodriguez, and was sergeant of all the district. Most of the Indians were naked; some were clothed with a linen dress, others in Spanish fashion with doublets and hose.

They are weak people, and have no arms, so that the Spaniards easily master them. They pay a tribute of three reals, that is a little less than three florins of Holland, a head, both men and women, of more than twenty years of age. There are very few Spaniards in each district; they have a priest for each, whom the inhabitants hold in great veneration, so much so, that it is only for want of priests if they do not hold all these islands in servitude, for there are even places where there are neither priests nor Spaniards, and nevertheless they cause the tribute to be paid there.

In the afternoon the admiral dismissed Enrique Nuñez and made him a respectable present, because they had obtained much fresh provisions through him: a sailor named James Lock, who spoke good Spanish, was ordered to go with him on shore. Every one in this country believed that these ships had a commission from the King of Spain, and without this belief the people would not have shown such good will.

On the 18th October they saw a Spanish captain and a priest come off to the ships. The captain had leave to come on board, but the priest remained in the canoe. After the first compliments, he asked the admiral to show him his commission, because it was forbidden them to trade with strangers. The general showed him the commission which he held from Prince Maurice [Stadtholder of the Netherlands], which caused him great astonishment, for he had thought these two ships from Acapulco, a port of New Spain.

As James Lock was still on shore, the general sent back one of the Spaniards with a letter, by which he asked for him to be sent back, failing which he would carry off in his stead the captain who was with him, and who was named Rodrigo Arias Xiron. Next day the priest came back, and asked of the admiral an assurance in writing to set free the captain as soon as Lock was restored to him; this was done, and some presents were also given to the captain.

After that time no more provisions were supplied: the Dutch had taken on board two Indians who were well known at Capul. The 20th, at dawn, they made for the Manila straits. On the 21st the Concord [Eendragt] found a Spanish vessel with twenty-five measures of rice and seven hundred fowls; the crew had abandoned it and fled. They unloaded it and sunk it: the Indian pilot said it belonged to a Spaniard, who was to take in some planks and go on to Manila."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

"Van Noort turned into the Pacific on 10 May, well before his former viceadmiral De Lint had left his vigil at Santa Maria. Charts provided for the Van Noort fleet must have shown Isla del Coco, an infrequently visited island. Van Noort steered for Coco, but with his accustomed skill failed to find it after an extensive search, so he gave it up and proceeded for the Ladrones, which would be his first landfall in the East. Along the way, he abandoned the Buen Jesus which had broken her rudder on 15 August, and on 28 August an unidentified prize for which he had no further use.

Shortly after that, he threw the coastal pilot, Juan de San Aval, captured from the Buen Jesus, over the side, a punishment usually reserved for pirates. The unfortunate man had accused Van Noort of trying to poison him to death, so Van Noort accommodated him, even though De San Aval had heretofore been treated with courtesy and took his meals with the officers.

In mid-June Van Noort found the easterly trade winds. He had a relatively easy passage to Guam, where he was greeted by 200 canoes, and was able to trade bits of iron for food. At Luzon, on 15 October, he pretended to be a French ship with permission to trade in the Indies, and was able to purchase rice, hogs and poultry. After three days his ruse was discovered by a Spanish official and he sailed on, more pirate than trader, looting every ship he found. On 21 October he captured a small [Spanish] bark loaded with rice and fowls and sank it."

(Swart's biography of Lambert Biesman)

"On the 16th October they came to Bayla bay [Baye la Bay, the Gulf of Albay in Luzon] in a very fertile land, at which place they procured abundance of all kinds of necessaries for their ships, by pretending to be Spaniards. The Spaniards, who are lords here, make the Indians pay an annual capitation tax, to the value of ten single rials for every one above twenty years of age. The natives of these islands are mostly naked, having their skins marked with figures so deeply impressed [tatooed], that they never wear out."

(Kerr)

"The expedition against the silver fleet, however, had to be given up. It would have been too dangerous. It became necessary to leave the eastern part of the Pacific and to cross to the Indies as fast as possible. The Spanish ship which had been captured in Valparaiso proved to be a bad sailor and was burned. The two Dutch ships, with a crew of about a hundred men, sailed alone for the Marianne Islands. Some travelers have called these islands the Ladrones. That means the islands of the Thieves, and the natives who came flocking out to the ships showed that they deserved this designation. They were very nimble-fingered, and they stole whatever they could find. They would climb on board the ships of Van Noort, take some knives or merely a piece of old iron, and before anybody could prevent them they had dived overboard and had disappeared under water. All day long their little canoes swarmed around the Dutch ships. They offered many things for sale, but they were very dishonest in trade, and the rice they sold was full of stones, and the bottoms of their rice baskets were filled with cocoanuts. Two days were spent getting fresh water and buying food, and then Van Noort sailed for the Philippine Islands. On the fourteenth of October of the year 1600 he landed on the eastern coast of Luzon. By this time the Dutch ships were in the heart of the Spanish colonies, and it was necessary to be very careful not to be detected as Hollanders. The natives on shore, who had seen them in the distance, warned the Spanish authorities, and early in the morning a sloop rowed by natives brought a Spanish officer.

Van Noort arranged a fine little comedy for his benefit. He hoisted the Spanish flag and he dressed a number of his men in cowls, so that they would look like monks. These peeped over the bulwarks when the Spaniard came near, mumbling their prayers with great devotion.

Van Noort himself, with the courtesy of the professional innkeeper, received his guest, and in fluent French told him that his ship was French and that he was trading in this part of the Indies with the special permission of his Majesty the Spanish king. He regretted to inform his visitor that his first mate had just died and that he did not know exactly in which part of the Indies his ship had landed. Furthermore he told the Spaniard that he was sadly in need of provisions and this excellent boarding officer was completely taken in by the comedy and at once gave Van Noort rice and a number of live pigs. The next day a higher officer made his appearance. Again that story of being a French ship was told, and, what is more, was believed. Van Noort was allowed to buy what he wanted and to drop anchor on the coast. To expedite his work, he sent one of his sailors who spoke Spanish fluently to the shore. This man reported that the Spaniards never even considered the possibility of an attack by Dutch ships so far away from home and so well protected by their fleet in the Pacific. Everything seemed safe.

But at last the Spaniards, who had heard a lot about the wonderful commission given to this strange captain by the King of France and the King of Spain, but who had never seen it, became curious. Quite suddenly they sent a captain accompanied by a learned priest who could verify the documents. It was a difficult case for the Dutch admiral. His official letters were all signed by the man with whom Spain was in open warfare, Prince Maurice of Nassau. When this name was found at the bottom of Van Noort's documents, his little comedy was over. Nobody thereafter was allowed to leave the ship, and the natives were forbidden to trade with the Hollander. Van Noort, however, had obtained the supplies he needed. He had an abundance of fresh provisions, and two natives had been hired to act as pilot in the straits between the different Philippine Islands."

(Van Loon)

2. A native Philippine Indian

Title: Ung habitant de lysle Capul [A native of the island of Capul]

Triptych of three ethnographic images of costumed figures, as observed by Van Noort during his circumnavigation. On the left is a Patagonian giant, with two penguins, seen in Magellan's Strait. On the right is an inhabitant of New Spain denoted as an "artisan".

The center figure is of special interest to the Philippines. He is labelled as "An inhabitant of the island of Capul", and we believe is the first printed depiction of a Philippine native.

Van Noort is very impressed with the tattoos of the indians. About the natives of the Philippines, Van Noort writes:

"The Indians are mostly naked, though some wear a linen cloth. There were also quite a number that were Spanialised, wearing throusers and shirts. And then there are the foremost Indians that descend from nobility, that have very nice and beautifully cut engravings on their skin, and because it has been engraved with iron and ink it can never be erased."

(Van Noort, our translation)

"On the three and twentieth, some went on Land, and eat Palmitos, and dranke water, after which followed the bloudie Fluxe, whether of this cause, or the landing after so long a being at Sea, uncertaine.

The foure and twentieth, they entred the straight and sayled by the Island in the midst, and in the Evening passed by the Isle Capul, seven miles within the straight, neere which they found many Whirle-Pooles, which at first seemed Shoalds but they could find no bottome. The people were all fled. Heere they lost a Londoner, John Caldwey (a Londener), an excellent Musician surprized, as was suspected, by some insidiarie Indians; whereupon they burned their Villages. Manilla is eightie miles from Capul, which now they left to attaine the other, but in a calme winde, with violent working of the waves, were much tossed without much danger, by reason of the depth. They wanted a Pilot, and their Maps were uncertaine."

(Purchas 1625 brief english summary version of Van Noort's Journal)

"The 24th they entered the Manila straits, and came near the isle of Capul, and anchored off a sandy bay and village to the west of the island. On the morning of the 25th they saw that the inhabitants of the village had run away. On the 27th, as no one appeared, the admiral sent some men on shore, and fired at the houses with large cannon to frighten the inhabitants. At the noise a Chinaman came from another village to the Dutch, who took him to the admiral. They could not understand him, but he made signs that he would bring provisions; and a present was given him, and he was promised money for anything he brought. The sailors who had gone on shore left there one of their number, named John Calleway, of London, a musician and player on instruments. They did not know how he had separated from them, and suspected that the Indians had attacked him on seeing him far from the others: one of the Indian pilots was also detained. The following night the other pilot, who had been taken in La Bahia, jumped into the water and escaped, in spite of the good treatment he had received from the admiral. He was named Francisco Tello, from the name of the governor of Manila, who had presented him at baptism. For the Spaniards act in that manner in that country: they pay some honour to the Indians when it costs them nothing, and give them even some small commission to win them over.

On the 28th the admiral landed with thirty-two men and caused several villages to be set on fire, whose inhabitants had run away with their property, so that nothing was found there, and no Indian made his appearance.

The night of the 22nd October the negro Manuel, who was on board the Concord [=Eendragt], got down into the boat and escaped, contrary to all the promises which he had made of remaining in the service of the Dutch. The admiral then had the other negro, named Sebastian, examined, who owned that he had been acquainted with the design of his comrade, and that he had had the same intention, but that he had not thought the opportunity which Manuel had availed himself of sufficiently safe.

The admiral, seeing the ingratitude of these negroes, and that all the good treatment practised towards them was of no use, and that they were always disposed and ready to betray the Dutch, ordered Sebastian's brains to be blown out with an arquebuse, so as not to be again exposed to his treasons. Before dying, he again said that all that the Spanish pilot and he had before declared respecting the gold which had been in the prize Buen Jesus was true.

The 31st October part of the crew went again on shore to seek for victuals: they found in a certain place more than thirty measures of rice, but they saw no one. Every one had run away to hide in the woods. They then again burned four villages, each of fifty or sixty houses.

On the 1st November the two Dutch ships again sailed for Manila: on the 5th they saw a canoe and sent a boat to fetch it; it contained nine Indians, two of whom they kept to show them the way to Manila, the rest were let go.

Letters were found in their possession, with an authorisation from the governor, under the seal of the King of Spain, which were addressed to a priest who lived in a place named Bovillan, sixty leagues from Manila. The contents of these letters were to the effect that complaints had been made to the governor on the subject of certain Spaniards who had much ill-treated the Indians; and the governor gave orders to the priest to take informations on these acts, and to transfer the guilty to Manila at the king's expense.

On the 6th November, after remaining for some days sheltered behind an island four leagues from Capul, on account of contrary winds and calms, they captured a boat which ran on shore, and the men escaped into the woods: this boat carried four Spaniards and some Indians, and was taking half a barrel of powder, a quantity of balls and pieces of iron: the admiral unloaded the boat and had it sunk. One of the Spaniards came, and, on the promise of the Dutch not to hurt him, let himself be taken on board: from him they learned that the boat was going to Soubon to go to make war on the Moluccas, whose people had been plundering some of the Philippines. On the 7th they saw a Chinese vessel of 100 or 120 tons, which they call a champan: the master of it, a Chinese of Canton, had learned Portuguese at Malacca, and was of great assistance to the Dutch; he informed them that there were two large ships of New Spain and a little Flemish vessel bought from people of Malacca anchored at Cabite [Cavite], the port of Manila, two leagues from it; that this port was defended by two forts, but that they then had neither cannon nor soldiers. He also said that the houses of Manila were very crowded, that the town was surrounded by a rampart. More than 15,000 Chinese live outside. Every year four hundred ships come from Chincheo in China with silks and other goods, and take silver coin in return; they came between Christmas and Easter. Also two ships were expected in November from Japan, with iron, flour and other victuals: there was a little island called Maravilla, about fifteen leagues from the town, with a good anchorage. From there it would be easy to reconnoitre the country.

On the 9th November the two ships weighed, and on the 11th they anchored half a league off an island named Banklingle. On the 15th, as they were still at anchor, they discovered two boats going to Manila with their cargoes as tribute. This adventure supplied them with two hundred and fifty fowls and fifty pigs, for which the admiral gave the Indians a few pieces of cloth and a letter to the governor of Manila, saying he would come and visit him. On the 16th they again set sail, and captured two canoes with thirty pigs and one hundred fowls going to Manila : the Indians were set free, and charged with another letter to the governor begging him not to take it ill that they carried off his tributes, because the Lord had need of them. The 21st the wind was so contrary that the two ships had to return to Banklingle: here they took another Chinese champan, quite new; the crew had escaped to the woods. During the night the champan, which had been taken before on the 7th, and in which James Thuniz had been put as pilot with five other Dutchmen and five Chinese, set sail; the crew called out to ask the admiral if they were to steer south. The admiral sent to tell them to stop and cast anchor again. It is not known what became of that champan, for it was not seen again : the Chinese were suspected of having cut the Dutchmen's throats and of having carried off the vessel. The master and pilot of the champan, who had been all this time detained on board the admiral's ship, made as much noise as if the Dutch had been the cause of this loss; they complained bitterly, and bore with impatience the loss of their champan and merchandise, protesting that they knew nothing of what had happened."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

"On 24 October he went ashore to a village in the Strait of San Bernardino [Manila Strait], and found the inhabitants had concealed themselves on their approach. John Caleway, the ship’s musician, was captured there and was never seen again. On 28 October Van Noort burned the village in retaliation. On 29 October, Bastien, one of the slaves captured from the Buen Jesus, deserted. His fellow slave, Emmanuel, was interrogated and Van Noort, not satisfied with Emmanuel’s answers, ordered the man shot. On 30 October a shore party landed and found more hidden rice and hogs, which they slaughtered. Four more villages, each of fifty to sixty houses were put to the torch. On 6 November Van Noort took a Spanish bark and sank it, and on 7 November took a Chinese sampan which he kept to use as a tender. He put aboard a prize crew of six men, leaving the five captured Chinese aboard. On the night of 21 November the sampan vanished, with no trace of his crewmen. When he got to Manila on 24 November he lurked outside the harbour, continuing his piracy.

Manila Bay is enormously large, able to contain all the navies of the world. The north channel to the bay is guarded by two islands; one, very close to the mainland, named La Monja, the other somewhat larger and on the right of the north channel, named Corregidor. There is another island, somewhat outside the bay and to the south, named Fortuna. Upon his arrival Van Noort placed his ships on the mainland side of the islands north of the channel where he concealed himself from view, both from the city and shipping entering the main channel. He called a meeting of the ships’council where he announced his plan to lie at the mouth of the bay until the beginning of February, intercepting all Manila-bound shipping and hoping for the arrival of the annual treasure ship from Panama, laden with silver to buy oriental tradegoods. If Biesman’s counsel advised against this course of action it would have availed little. There Van Noort lay in wait with Biesman, we hope, his unwilling accomplice, using the islands to conceal themselves from view.

The progress of Van Noort and Biesman had been so leisurely that word of their presence had preceded them. The governor, Don Francisco de Tello, had already ordered the conversion of two ships for the defence of the port: one, an embargoed cargo ship still laden with its consignment named San Antonio de Zebu (Cebu), the other a small galleon still under construction, the San Bartolomé. The work on the conversion had already begun when the Dutchmen arrived at Manila.

Dr Antonio de Morga, a judge of the Audiencia, begged Governor de Tello to appoint him over the officer who was currently engaged in the project to complete the conversion of the ships. De Morga was hard to refuse, and the governor awarded him the post. To his credit, De Morga expedited the work on the two ships, but in the haste necessitated by the presence of the two corsairs at their door, the San Antonio was not offloaded of its heavy cargo. As a consequence, mounting the necessary guns on her upper decks caused dangerous instability. The ship lay so low due to her excess weight that the lower, lee-side gun ports could not be opened without water flooding into the ship. The smaller ship did not present this problem, but her keel had only recently been laid and much work was necessary to ready her for the sea.

De Morga cajoled the governor to name him the General of the armada, with the San Antonio his Capitano, or flagship, even though he had little or no fighting experience, a fact he concealed from the governor. The governor had doubts, but De Morga prevailed. Second in command was a proper fighting man, Juan de Alcega, vice admiral, with the San Bartolomé his Almirante, or vice-admiral’s ship. Van Noort and Biesman continued their depredations, unaware that the sound of hammering and sawing coming from behind the Cavite peninsula had any relevanceto them."

(Swart's biography of Lambert Biesman)

"Being discovered to be Dutch, but not till they had gained their ends, they sailed for the Straits of Manilla, all the coasts near which appeared waste, barren, and rocky. Here a sudden squall of wind from the S.E. carried away some of their masts and sails, being more furious than any they had hitherto experienced during the voyage. The 23rd some of the people went ashore, where they eat palmitoes and drank water so greedily, that they were afterwards seized with the dysentery. The 24th they entered the straits, sailing past an island in the middle, and came in the evening past the island of Capul, seven miles within the straits, near which they found whirlpools, where the sea was of an unfathomable depth, so far as they could discover."

(Kerr)

"The next few weeks Van Noort actually spent among those islands, and with his two ships terribly battered after a voyage of more than two years of travel he spread terror among the Spaniards. Many ships were taken, and landing parties destroyed villages and houses. Finally he even dared to sail into the Bay of Manila. Under the guns of the Spanish fleet he set fire to a number of native ships, and then spent several days in front of the harbor taking the cargo out of the ships which came to the Spanish capital to pay tribute. As a last insult, he sent a message to the Spanish governor to tell him that he intended to visit his capital shortly."

(Van Loon)

3. Encounter with a ship from Japan

Title: Ung batteau de Iapan diit Champan [A ship from Japan which they call Champan]

"On the third of December while we were at anchor [outside Manila Bay], we became aware of a big sail on the horizon. The yacht [Eendragt] met them and brought their captain and some of the officers to our admiral [Mauritius]. It was one of the ships from Japan, of which the Chinese captain had told us. They were mostly carrying iron and flour which they load in Japan and come to Manila to sell. Their ship was about 50 last in size and had left Japan 25 days ago, accompanied by three other ships that the lost sight of in a tempest. The ships are of a very strange design. The front is flat like a chimney. The sails are made of reed mats, they have wooden anchors, and the cordage is made of straw. They are very skillful in sailing them."

(Van Noort, our translation)

"The seventh of November, they tooke a China Junke, laden with provision for Manilla. The owner was of Canton, the Master and Mariners of Chincheo. This Master was expert in the Portugall tongue, and their Indian affaires, which happened verie luckily to the Hollanders ignorant of their course. These told them that in Manilla were two great Shippes, which from new Spaine yeerely sayled thither; that there was also a Dutch Shippe bought at Malacca: These ride before Manilla, and there are two Castles or Forts to secure them; the Citie also walled about, and without it above fifteene thousand Chinois Inhabitants, occupied in marchandize and handycrafts : And that foure hundred China Shippes come thither yeerly from Chincheo, with Silke and other precious marchandise, betwixt December and Easter. They added that two were shortly expected from Japon with Iron, other mettalls and victualls.

On the fifteenth, they tooke two Barkes laden with Hennes and Hogges, which were to bee paid for tribute to the Spaniards, for which they gave them some linnen bolts in recompence. They passed by the Isle Bankingle, and another called Mindore, right against which is the Isle Lon-bou, two miles distant, and betwixt them both, is another lesser Island, neere which is safe passage for Ships.

They agreed upon consultation to stay in expectation of the Japonian Ships, at an Anchor (for the East wind hath the Monarchy of that season in those parts) in fifteene degrees of North Latitude. The Isle Lusson is bigger then England and Scotland, to which many Islands adjoyne. The riches arise more out of trafficke, then fertilitie. On the third of December they tooke one of the Japon Ships of fiftie tunnes, which had spent five and twentie dayes in the voyage. The forme was strange, the forepart like a Chimney, the sayles of Reed, or Matt twisted, the Anchors of Wood, the Cables of Straw."

(Purchas 1625 brief english summary version of Van Noort's Journal)

"On 3 December Van Noort stopped a Japanese vessel bound for Manila, laden with flour, iron, fish, and hams. Van Noort uncharacteristically purchased provisions from her, as well as a well-made wooden anchor, and let her go on her way. On 9 December he took a Spanish vessel with a cargo of coconut wine and a Chinese sampan with a cargo of rice. Both he sank."

(Swart's biography of Lambert Biesman)

"On the 24th the ships came to the bay of Manila, and could not fetch the island Mirabilis, and anchored on the west side of the bay, behind a point twelve leagues from the town.

On the 3rd December, 1600, the admiral's ship was at anchor, and the Concord [Eendragt]under sail: she discovered a large ship and captured her, and brought the captain and some of the chief men of the crew aboard of the admiral. It was one of the Japanese ships which the Chinese master had said was coming. The admiral received the Japanese captain well, his name was Jamasta Cristissamundo: the admiral asked him for some provisions, on which he sent twenty-nine baskets of flour, eight baskets of fish, some hams and a wooden anchor with its cable. The admiral gave him three muskets and some pieces of stuff: he also asked for a passport and flag, and the admiral gave him one in the name of Prince Maurice. In acknowledgment the captain gave him a Japanese boy of eight years old: he then made for Manila."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

"They now crowded sail for Manilla, which is eighty miles from Capul, but wanted both a good wind to carry them, and good maps and a skilful pilot to direct them to that place. The 7th November they took a junk from China, laden with provisions for Manilla. The master of this junk told them there were then at Manilla two great ships, that come every year from New Spain, and a Dutch ship also which had been brought from Malacca. He said also that the town of Manilla was walled round, having two forts for protecting the ships, as there was a vast trade to that place from China, not less than 400 junks coming every year from Chincheo, with silk and other valuable commodities, between Easter and December. There were also two ships expected shortly from Japan, laden with iron and other metals, and provisions. The 15th they took two barks, laden with hens and hogs, being part of the tribute to the Spaniards, but became food to the Dutch, who gave them a few bolts of linen in return.

They passed the islands of Bankingle and Mindoro, right over against which is the island of Lou-bou. at the distance of two miles, and between both is another small island, beside which there is a safe passage for ships. The island of Luzon is larger than England and Scotland [Luzon is certainly a large island, but by no means such as represented in the text], and has a numerous cluster of small islands round about it; yet is more beholden to trade for its riches, than to the goodness of its soil. While at anchor, in 15° N. waiting for the ships said to be coming from Japan, Van Noort took one of them on the 1st December, being a vessel of fifty tons, which had been twenty-five days on her voyage. Her form was very strange, her forepart being like a chimney, and her furniture corresponding to her shape; as her sails were made of reeds, her anchors of wood, and her cables of straw. Her Japanese mariners had their heads all close shaven, except one tuft left long behind, which is the general custom of that country. The 9th, they took two barks, one laden with cocoa wine and arrack, and the other with hens and rice."

(Kerr)

4. Depiction of the Japanese sailors

Title: La comune accoutre ala polonoise. Ung Capitaine de Iapan

"The General (Van Noort) treated the Captain very well. He was a born Japanese, named Iamasta Cittisamundo. They wear long garments much like the Polish. The Captains clothes (who was a nobleman) were of light silk, painted very artistically with all kinds of foliage and flowers. And all the Japanese are shaved bald with a razor, except in the neck where their heir grows long. They are a very courageous people in war and are of large stature. In Japan the best arms in all of the East Indies are made, swords, guns, bows and arrows, of which they gave us some. The swords are of exceptional sharpness, they told us that in Japan there are swords that can cleave three men in one single slash. When selling these swords they occasionally prove it by demonstrating it on some slaves."

(Van Noort, our translation)

"The Japanders make themselves bald, except a tuft left in the hinder part of the head. The Jesuites have the managing of the Portugall trafficke in Japon, having made way thereto by their preaching, and are in reputation with their converts, as Demi-gods: neither admit they any other order of Religion to helpe them. The Generall obtained at easie rate one of these woodden Anchors for his use, and some quantitie of provision. On the ninth, they tooke a Barke laden with Coquo Wine, like Aqua-vitae, the people all fled; and another with Rice and Hennes."

(Purchas 1625 brief english summary version of Van Noort's Journal)

"On the 24th the ships came to the bay of Manila, and could not fetch the island Mirabilis [Corregidor Island], and anchored on the west side of the bay, behind a point twelve leagues from the town. On the 3rd December, 1600, the admiral's ship was at anchor, and the Concord [Eendragt] under sail: she discovered a large ship and captured her, and brought the captain and some of the chief men of the crew aboard of the admiral. It was one of the Japanese ships which the Chinese master had said was coming. The admiral received the Japanese captain well, his name was Jamasta Cristissamundo: the admiral asked him for some provisions, on which he sent twenty-nine baskets of flour, eight baskets of fish, some hams and a wooden anchor with its cable. The admiral gave him three muskets and some pieces of stuff: he also asked for a passport and flag, and the admiral gave him one in the name of Prince Maurice. In acknowledgment the captain gave him a Japanese boy of eight years old: he [the Japanese ship] then made for Manila.

On the 9th the Concord (Eendragt) brought in a boat loaded with wine, which the Spanish crew had abandoned: the wine tasted like the spirits made from a kind of cocoa nut; the wine was divided between the two ships, and the boat sunk: more boats with fowls and rice were captured."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

5. The naval battle of Manila Bay

Title: La bataille d'autre nous et contre cieux de Manille faicte le 14 Decembre anno 1600 [The battle between us and those of Manila on 14 December of the year 1600

A dramatic and very deadly naval battle took place between Van Noort and two heavily armed Spanish Galleons commanded by Don Antonio de Morga, the Spanish Vice Governor of the Philippines. The battle took place off Fortune Island, southwest of Manila.

In the front is the large Spanish Admiral flag ship 'San Diego' (A) engaged with Van Noort's much smaller 'Mauritius' (B). The Spanish Vice-Admiral ship (C) is chasing the tiny pinnace 'Eendragt' (D). Two native junks (E), who had been enlisted by the Spanish to engage in the fight, were too afraid to participate.

The deck between the fore- and aft castle is named the 'pit', and the Dutch had covered it with a 'pirate's net' (boevennet), also refered to as bulwark nettings, a tight grid made of ropes, meant to prevent pirates and enemies that board your ship to enter the pit, while at the same time allowing the crew to bombard the intruders from the fore- and rear castles and from below with guns, pikes and swords. The Spanish Admiral ship had dropped their main anchor into Van Noort's pirate's net, where it got so entangled that it was almost to separate the ships, even if the Spanish wanted too.

"By the 24th of November, Van Noort anchored off Manila Bay, at Corregidor Island, with the plan to trade with Chinese or Japanese ships that would arrive, in order to make his trip a commercial success. Three long weeks passed by. Unknown to Van Noort, the Spanish Vice Governer de Morga was transforming two large Galleons of the Manilla-Acapulco trade into warships by outfitting them with guns from Manila castle and preparing hundreds of soldiers to man them.

The Spanish admiral ship 'San Diego', which was 4 times larger Van Noorts 'Mauritius' and outnumbered his crew by 7 or 8 to 1, used grapple hooks to attach themselves to the Dutch ship. The two ships kept discharging their cannons below deck into each other. Hundreds of Spanish soldiers with gilted helmets and armour furiously boarded Van Noort's ship, certain of their victory.

"On the 24th November Van Noort arrived off the Bay of Manilla, where he remained, capturing and destroying vessels making the port of Cavete. On the 14th December two Spanish ships fitted as men-of-war, having on board a large force of men under the command of Antonio de Morga, the Lieutenant-governor and Judge (noted also as the historian of the Philippine Islands) came out of port to engage the Mauritius and Eendracht which at this tune had Crews respectively of fifty-five and twenty-five men.

A severe action ensued, during which the Spaniards were masters of the deck of the Mauritius but were ultimately repulsed by the brave Dutchmen, who opened fire again with their cannon and sank the admiral's ship, slaughtering those of the crew that sought refuge with them or swam about the sea. Others were taken to the shore by native boats. In this action the Spanish lost in killed fifty men, according to De Morga's confession, and the Mauritius five killed and twenty- six wounded. The Eendracht was captured by the Spanish almiranta, and taken to Manilla, where Captain Lambart Biesman and all his crew (25 total) were executed [garroted] as pirates."

(Rathbone)

“On the 9th the Concord [Eendragt] brought in a boat loaded with wine, which the Spanish crew had abandoned: the wine tasted like the spirits made from a kind of cocoa nut; the wine was divided between the two ships, and the boat sunk: more boats with fowls and rice were captured.

The morning of the 14th December, which was a Thursday, when they had their topmasts struck, they saw two sail come out of the straits of Manila, they took them at first for frigates; but as they approached it was seen that they were large ships, and it was known that they came to challenge. At once the topmasts were raised, and the artillery and other arms were got in readiness to receive them.

The Manila admiral, who had taken the van, came within range of the cannon of the Dutch; and after that these had discharged their broadside, he came and grappled with the Dutch ship, and part of his crew sprung on board of her, with a furious mien, carrying shields and gilded helmets, and all sorts of armour; they shouted frightfully, 'Amayna Perros, Amayna,' that is to say, 'Strike dogs, strike your sails and flag.'

The Dutch then went down below the deck, and the Spaniards thought they were already masters of the ship, the more so, that they were seven or eight to one. But they saw themselves all at once so ill treated with blows of pikes and musketry, that their fury was not long in slacking. Indeed, there were soon several of them stretched dead upon the deck.

However the Spanish vice-admiral was also bearing down upon the Dutch admiral, but there is much probability that he thought that his countrymen had already gained the mastery, for he went off in chase of the yacht, which had set her topsails and had gone to leeward of the admiral.

The Manila admiral remained all day grappled with the Dutchman, because his anchor was fast in the cordage before the mast of the latter, and the anchor tore the deck in several places, which left the Dutch crew much exposed. Meantime the Spaniards frequently discharged their broadsides at them, and the others did not fail to answer them. But at last the Dutch began to slacken their fire, seeing that there were already a great many of them wounded.

The [Dutch] admiral having perceived this slackness, went below the deck, and threatened his crew to set fire to the powder if they did not fight with redoubled ardour. This threat had its effect: they regained courage, and there were even some wounded men who got up and returned to the fight.

On the other side the enemy was not less disheartened, and part of his men had abandoned the Dutch ship. There were close by two Chinese champans full of people, but they did not venture to come any nearer on account of the cannon. So the Spanish crew, instead of continuing their attack, only made efforts to cast loose, in doing which they had very great difficulty."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

“The morning of the 14th December, which was a Thursday, when they had their topmasts struck, they saw two sail come out of the straits of Manila, they took them at first for frigates; but as they approached it was seen that they were large ships, and it was known that they came to challenge. At once the topmasts were raised, and the artillery and other arms were got in readiness to receive them.

The Manila admiral, who had taken the van, came within range of the cannon of the Dutch; and after that these had discharged their broadside, he came and grappled with the Dutch ship, and part of his crew sprung on board of her, with a furious mien, carrying shields and gilded helmets, and all sorts of armour; they shouted frightfully, 'Amayna Perros, Amayna,' that is to say, 'Strike dogs, strike your sails and flag.'

The Dutch then went down below the deck, and the Spaniards thought they were already masters of the ship, the more so, that they were seven or eight to one. But they saw themselves all at once so ill treated with blows of pikes and musketry, that their fury was not long in slacking. Indeed, there were soon several of them stretched dead upon the deck.

However the Spanish vice-admiral was also bearing down upon the Dutch admiral, but there is much probability that he thought that his countrymen had already gained the mastery, for he went off in chase of the yacht, which had set her topsails and had gone to leeward of the admiral.

The Manila admiral remained all day grappled with the Dutchman, because his anchor was fast in the cordage before the mast of the latter, and the anchor tore the deck in several places, which left the Dutch crew much exposed. Meantime the Spaniards frequently discharged their broadsides at them, and the others did not fail to answer them. But at last the Dutch began to slacken their fire, seeing that there were already a great many of them wounded.

The [Dutch] admiral having perceived this slackness, went below the deck, and threatened his crew to set fire to the powder if they did not fight with redoubled ardour. This threat had its effect: they regained courage, and there were even some wounded men who got up and returned to the fight.

On the other side the enemy was not less disheartened, and part of his men had abandoned the Dutch ship. There were close by two Chinese champans full of people, but they did not venture to come any nearer on account of the cannon. So the Spanish crew, instead of continuing their attack, only made efforts to cast loose, in doing which they had very great difficulty."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

"Van Noort then got ready to depart for further conquest. He had waited just a few hours too long and he had been just a trifle too brave, for before he could get ready for battle his ships were attacked by two large Spanish men-of-war. The Mauritius was captured. That is to say, the Spaniards drove all the Hollanders from her deck and jumped on board. But the crew fought so bravely from below with guns and spears and small cannon that the Spaniards were driven back to their own ship. It was a desperate fight. If the Hollanders had been taken prisoner, they would have been hanged without trial. Van Noort encouraged his men, and told them that he would blow up the ship before he would surrender. Even those who were wounded fought like angry cats."

(Van Loon)

"Van Noort dallied too long and had not set a diligent watch. On 14 December Van Noort espied two sail in the passage, standing out of the bay. He sent a boat to the Eendracht with orders to intercept them and speak to them, but it soon became apparent that these were vessels of war. He ordered the boat back and began to ready himself for combat. The vessels were very near and Van Noort was left with no time to draw up his [stuck] anchor. He severed the line and abandoned it. He met the San Antonio outside the bay and to the south, not far from Fortuna Island. Van Noort could muster fifty-three men on board the Mauritius; Biesman, in the Eendracht, twenty-four or five. By Van Noort’s account, each of the Spanish vessels was manned with 400 to 500 men. Such a claim is preposterous, but there may well have been near half that number. In turn, De Morga’s account inflates the strength of the Dutch ships’ manning and size. Van Noort ordered Biesman to stand off and avoid the battle.

Van Noort fired on the approaching Capitano, but she could not reply as her lower ports were awash and Van Noort was in her lee. The Dutch cannon wrought great destruction in her bows, so De Morga, unable to respond, ordered the helmsman to steer for the Mauritius and ram her at full speed, further weakening her already damaged bow. When this was done, the Spanish soldiers clambered aboard the Mauritius and drove the Dutchmen into the fore- and stern-castles. Now in control of the decks, the Spanish struck the Dutch colours and lowered the main and mizzen sails and removed their rigging. Biesman, seeing his commander’s colours struck, attempted to flee. Alcega, also noting the struck colours, assumed the Mauritius had surrendered, so rather than engaging the Mauritius from her other side as written in his detailed instructions, he pursued the Eendracht instead."

(Swart's biography of Lambert Biesman)

"The 14th of December they met the two Spanish ships returning from Manilla to New Spain, on which a very sharp engagement took place. Overpowered by numbers, the Dutch in the ship of Van Noort were reduced to the utmost extremity, being at one time boarded by the Spaniards, and almost utterly conquered; when Van Noort, seeing all was lost without a most resolute exertion, threatened to blow up his ship, unless his men fought better and beat off the Spaniards. On this, the Dutch crew fought with such desperate resolution, that they cleared their own ship, and boarded the Spanish admiral, which at last they sunk outright. In this action the Dutch admiral had five men slain, and twenty-six wounded, the whole company being now reduced to thirty-five men. But several hundreds of the Spaniards perished, partly slain in the fight, and partly drowned or knocked in the head after the battle was over. But the Dutch lost their pinnace, which was taken by the Spanish vice-admiral; and this was not wonderful, considering that she had only twenty-five men to fight against five hundred Spaniards and Indians."

After this action, Van Noort made sail for the island of Borneo, the chief town of which island is in lat. 5° N. while Manilla, the capital of Luçon, is in lat. 15° N."

(Kerr)

"On December 14, 1600, about 50 kilometers southwest of Manila, the Spanish battleship San Diego clashed with the Dutch ship Mauritius.

The San Diego was formerly known as San Antonio, a trading ship built in Cebu under the supervision of European boat-builders. It was docked at the port of Cavite to undergo reconditioning and repair but at the end of October 1600 Don Antonio de Morga, Vice-Governor General of the Philippines, ordered it converted into a warship and renamed it San Diego.

All odds were in favor of the Spanish. The San Diego was four times larger than the Mauritius, it had a crew of 450 rested men and massive fire power with 14 cannons taken from the fortress in Manila.

Unfortunately, this was also the weakness of the San Diego. Morga had the ship full of people, weapons and munitions but too little ballast to weigh the ship down for easier maneuverability. While the gun ports had been widened for more firing range, not one cannon could be fired because water entered through the enlarged holes.

The San Diego sprung a leak beneath the waterline either from the first cannonball fired by the Mauritius or from the impact of ramming the Dutch at full speed. Because of inexperience, Morga failed to issue orders to save the San Diego. It sank “like a stone” when he ordered his men to cast off from the burning Mauritius.

The events were recorded in Morga’s book, Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, where it portrayed Morga as a hero of the battle.

The accounts of the battle of the San Diego and the Mauritius are incomplete. To rectify this, Patrick Lize, a historian, conducted extensive research in the archives of Seville, Madrid, and The Netherlands to look for new information that would shed light on the battle. From the testimony of 22 survivors, memoirs of two priests from Manila and the inventory of both the weapons and provisions on the San Diego, a more accurate reconstruction of the battle was made possible.

Franck Goddio and his team, in coordination with the National Museum and financially supported by Foundation Elf, conducted underwater explorations to find the San Diego. They discovered the wreck about 50 meters deep near Fortune Island, outside of Manila Bay. It was undisturbed and formed a sand-covered hill of 25 meters long, 8 meters wide and 3 meters high. A cannon rising out of the sand with the inscription “Philip II” made the identification easier.

At enormous expense and with modern underwater technology and a team of 50, the San Diego was recovered. From the start, scientists from the National Museum of the Philippines and the Musée national des arts asiatiques in Paris, inventoried all the artifacts and took care to ensure the best possible conservation condition."

(Wikipedia)

6. The Admiral ship sunken

Title: L'admiral estant surmonte s'en allant au fondou a nostre veue [The (Spanish) admiral ship overcome and sunk before our eyes]

Hundreds of Spanish soldiers and sailors drown before the eyes of the Dutch. Many try to swim to the heavily damaged and burning Dutch ship but are spiked and gunned by the Dutch.

Signed by master engraver Benjamin Wright in the lower right (B.W. caela[vit]).

"On the fourteenth [December 1600], the Ships came from Manilla, and there passed betwixt them a Sea-fight. The Spanish Admirall [San Diego] came so neere, and was stored with men, that they entred the Dutch Admirall [Mauritius], and thought themselves Masters thereof, sixe or seven still laying at one Hollander: the Vice-Admirall also set upon the smaller Ship [Eendragt].

All day the two Admiralls were fast together, and the Dutch over-wearied with multitudes, were now upon point and to yeeld, when the Admirall [van Noort] rated their cowardise, and threatned to blow them up with Gun-powder presently.

This feare expelled the other, and the dread of fire, added reall fire to their courages, insomuch that they renued the fight, and cleared the Ship of her new Masters, which had no lesse labour to cleare their owne Shippe from the Dutch, which was no sooner done, but the Sea challenged her for his owne, and devoured her in one fatall morsell, into his unsatiable paunch. The people swamme about, crying, Misericordia, Misericordia, which a little before had cried in another dialect, Maina peros, Maina peros. Of these miserable wretches were two hundred, besides such as were before drowned or slaine.

But the fire was almost as dangerous to the Dutch, as the water to the Spanish ; by often shooting, the Timbers being over-heat, threatned by light flames to make the Dutch accompanie the Spaniards into Neptunes entrailes. But feare awaked diligence, and diligence cast this feare also into a dead sleep, the blessed Trinitie in almost an unitie of time, diverting a trinitie of deaths, by yeelding, sinking, firing. But in this divine mercie, they forgate not their inhumane feritie to the swimming remainders of the enemie, entertaining them with Pikes, Shot, yea (especially a Priest in his habite) with derision. In the Shippe were five Spaniards found dead with silver Boxes about them, containing little consecrated Schedules, testimonies of great and bootlesse superstition, in which they exceed the Europaean Papists, in the midst of Spaine and Rome."

(Purchas 1625 brief english summary version of Van Noort's Journal)

"However, the Dutch kept discharging their heavy guns upon the ship: at last the Manila admiral got away, and a little while after he was seen to sink, which he did so fast that he went down almost in the twinkling of an eye, and disappeared entirely, masts and all. Then the Spaniards were to be seen trying to prolong their life by swimming and crying out Misericordia, seeming to be about two hundred, besides those who were already drowned or killed.

The Dutch squared their fore yard, for their main yard had been cut down and their shrouds cut away. But what alarmed them most was the fire, which, from the continual discharges which they had made, had caught between decks, so much so that they had reason to fear that all would be burned. They succeeded, however, in extinguishing it, and then they rendered their prayers of thanksgiving to God, who had delivered them from so many dangers.

When they saw themselves out of danger they lay to, to repair damages, passing amongst many of their enemies who were still swimming, and whose heads, which appeared above water, they pushed under whenever they could reach them. Two dead bodies of Spaniards had remained on board: upon one of them was found a small silver box, in which were little papers full of recommendations and devotions to various Saints, men and women, to obtain their protection in perils."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

"Van Noort attempted to negotiate terms of surrender. No one in authority responded, and so the Dutch waited. As the hours dragged by, Van Noort realised that something was amiss. In his account of the battle he claims that the Dutch were fighting the whole time. The Spanish attack seemed now to be without direction. Six hours into the encounter Van Noort set a fire below decks which he knew that he could, with luck, extinguish and ordered his men out of the shelter of the castles, threatening to let the ship blow if they did not resume the fray. The Spanish soldiers fled in panic back to the San Antonio upon seeing the smoke. When De Morga was informed that the Dutch ship was on fire he ordered immediate withdrawal and release of the grapples from the sides of the Mauritius. This done, the San Antonio sank after sailing only a few hundred yards. She had gradually been filling by her bows with water, unknown or ignored by De Morga, and may even have been temporarily stabilised by the grappling lines, which were now severed."

(Swart's biography of Lambert Biesman)

"At last a lucky shot from the Mauritius hit the largest Spaniard beneath the water-line. It was the ship of the admiral of Manila, and at once began to sink. There was no hope for any one on board her. In the distance Van Noort could see that the Eendracht, which had only twenty-five men, had just been taken by the other Spanish ship. With his own wounded crew he could not go to her assistance. To save his own vessel, he was obliged to escape as fast as possible. He hoisted his sails as well as he could with the few sailors who had been left unharmed. Of fifty-odd men five were dead and twenty-six were badly wounded. Right through the quiet sea, strewn with pieces of wreckage and scores of men clinging to masts and boxes and tables, the Mauritius made her way. With cannon and guns and spears the survivors on the Mauritius killed as many Spaniards as possible. The others were left to drown. Then the ship was cleaned, the dead Spaniards were thrown overboard, and piloted by two Chinese traders who were picked up during the voyage, Van Noort safely sailed for the coast of Borneo."

(Van Loon)

7. Manila Bay and the capture of our brigantine

Title: Description de Manille avecq la prise de nostre brigantine [Description of Manila with the capture of our pinnace]

Manila Bay and castle are shown. Van Noort's ship 'Mauritius' is on the left. The print is decorated with a monster fish and a giant octopus.

Signed by master engraver Benjamin Wright.

The Dutch lost their yacht 'Eendragt', which was taken by the Spanish vice-admiral and towed into Manila harbour (in the right of the image); this was not surprising, considering that she had only twenty-five men to fight against five hundred Spaniards and Indians. Captain Lambert Biesman plus his crew of 24 were executed in Manila for piracy.

"On the side of the Dutch there were seven men killed and twenty-six wounded, so that on board the admiral there remained only forty-eight persons, both of wounded and sound. When they got the ship under sail, they saw the Manila vice-admiral and the yacht Concord at more than two leagues off; and they thought the Spaniards had got possession of her, because it seemed to them that her flag was down, and that the Manila flag was still flying. Besides, they did not consider it possible for the yacht, which no longer had more than twenty-five men of the crew, including ship-boys, and which was a weak ship, to resist such a ship, which was fully of six hundred tons burden.

The two Spanish ships had each crews of about five hundred men, both of that nation and Indians, and ten pieces of cannon. They were the same ships which go every year from Manila to Mexico, laden with silk and other rich merchandise. They had been armed to drive away the Dutch from these coasts, where they will not permit any foreign nation to come and traffic, and a crowd of Indians had been employed in them, who, having been instructed by the Spaniards, knew well how to handle a musket and other arms. The governor of Manila and of all the Philippines was named Don Francisco Tello de Meneses.

The admiral having saved himself by his valour and by that of his men, made his course towards the island of Borneo, which is one hundred and eighty leagues from Manila, to refresh his crew there and refit his ship, which was in novise in condition to sustain an attack from the Spanish vice-admiral, or to disengage the yacht."

(Stanley's abridged translation of Van Noort's Journal)

"Five Hollanders were slaine and twentie six wounded in the fight, the whole company in the Ship being but five and thirtie. The Pinnasse had but five and twentie, and could not withstand the violence of five hundred armed men in the enemies Vice-Admirall, some Spaniards, some Indians, which after long fight tooke her. These two were the Mexican Shippes, which yeerely trade in the Philippinas for Silke, Gold, and Muske, with other commodities of China."

(Purchas 1625 brief english summary version of Van Noort's Journal)

"Alcega pursued the Eendracht and overtook her after a chase of several hours. Five or six of the Eendracht’s men were killed in the ensuing battle for the ship. At the end, Biesman stood in front of the magazine with a burning brand, ready to die rather than surrender. Alcega assured him that he and the crew would be treated with compassion and their lives spared if they would submit, and so achieved their surrender. Alcega returned to Manila in company with the captured Eendracht and her crew, where they were turned over to the governor. It seems fair to say that Van Noort, having suffered many casualties himself and his ship badly damaged, could offer little help to Biesman had he tried. The Spanish force on the San Bartolomé was much superior in numbers and well armed, even though the ship was hardly larger then the Eendracht. De Morga censured Alcega severely for not attacking Van Noort and blamed him for the loss of the San Antonio. Had Alcega attacked it seems likely that he would also have taken the Mauritius, but it is not likely he could have saved the San Antonio.

Van Noort quickly extinguished the fire and set about setting his ship to rights. In a short time he had his ship under control, rigged a foremast sail and set about sailing through the horde of Spanish swimmers, his men shooting and stabbing with pikes all they could reach. Many of the Spaniards were wearing heavy armour which impeded swimming. De Morga later wrote that he swam with the captured [Dutch] colours in his armour for four hours before reaching Fortuna Island. He reported that fifty of the Spaniards drowned. Van Noort claimed that 150 of them drowned or were killed. Van Noort sailed slowly away after clearing the swimmers, making his way to Brunei, where he narrowly escaped an attempt by the ruler there to capture his ship. From Brunei he endeavoured to reach Bantam and failed, then sailed southeast through the Java Sea, stopping near Bali for a few bags of pepper. From there he sailed home with his forty-eight survivors.

According to De Morga the battle for control of the deck of the Mauritius waged fiercely for six hours. Other authorities dispute this assertion, which De Morga disseminated throughout the Spanish speaking world in an apologia [Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas] for his conduct of the battle. An examination was held by a court of inquiry after the battle, and testimony obtained from sailors who were aboard the San Antonio (rechristened the San Diego after her refit, by which name her wreck is identified) reveals that De Morga cowered behind the capstan in a roll of kapok, trembling with fear and unable to communicate other than to ask his subordinates, ‘But what can I do?’. When he at last comprehended that the Mauritius was on fire, he, barely lucid, ordered the San Antonio to withdraw immediately, by which time she was no longer buoyant.

At the very least De Morga exaggerated his military experience to the governor, and he it is clear that he sought the command only in order to add lustre to his reputation.

Nineteen men, including Biesman, were imprisoned at Manila. The Spanish authorities quickly secured all of the documents, commissions, and orders pertaining to the ship. It did not help Biesman’s case that the commisie-brief for the commander of the ship was made out in favour of Pieter de Lint, who now commanded the Hendrik Frederik. Van Noort had not written a new commission or endorsed the old one, so Biesman had no written authority to be commanding the Eendracht. The Spanish, who documented everything, translated the commission papers into Spanish, and the translation is the only copy that survives. In it, the Eendracht is named Concordia and De Lint, Isayas de Lende.

According to De Morga’s account, Biesman and his crew were executed by order of the governor, Don Francisco de Tello, without trial, customary for pirates. Alcega’s assurances that their lives would be spared, if they were communicated to the governor at all, were ignored. The prisoners were examined, and six of the youngest were spared upon their acceptance of the Roman faith: most of the Netherlands had until recently been Catholic, and the majority of them had not abandoned that faith, as many have not to this day. Some of the young prisoners were likely not guilty of apostasy at all, but loyal to the Holy Church from the start (of the six, two were known to have served in Spanish galleys). The rest, thirteen in all, were given the choice to foreswear the reformed religion so that they might die in a state of grace and be awarded a less painful death. Biesman alone refused, unshakable in his conviction. The means of death meted out to the twelve is unrecorded. Biesman was taken to the garrotting post and there he died. The priests who witnessed the execution called him ‘the most hardened heretic that they had in their lives yet encountered’.

Lambert Biesman might be seen by many to be a minor character on the world stage. He can not be said to have discovered anything of note, nor has he left a legacy of his observations or descriptions of his travels to inform future generations. Only his seven letters [to his parents and siblings in Nijmegen] survive, and they reveal an engaging young man, eager to embrace the adventure of life. However, his bravery, his sacrifice, and his participation in the Netherlands’ two most significant voyages of discovery [Houtman 1595-97 and van Noort 1598-1601], whereupon was laid the foundations both of the most powerful commercial empire in history, and of an acquisition of wealth never before seen in the world, surely merit him a place in the hall of heroes of the Netherlands, to be honoured there forever."

(Swart's biography of Lambert Biesman)

The Dutch Terrorized the Philippines in 1600 Before Circumnavigating the World

"In 1600, two Dutch ships terrorized the Philippines. They then went on to become the fourth group of Europeans to circumnavigate the world.

This is recorded in “Events of the Philippine Islands,” published in Mexico in 1609. Praised by historians, it describes the Philippines in not only the early years of Spanish occupation but also the bravery of its Spanish vice-governor in fighting off the Dutch… sort of.

In the 1500s, three expeditions (led by Ferdinand Magellan, Francis Drake, and Thomas Cavendish) had already circumnavigated the world. The Dutch wanted to do the same so, in 1598, they raised two fleets. One was to establish a presence in the Spice Islands (in Indonesia), and the other to open trade with China and more Southeast Asian countries. There was, however, a problem. Spain and Portugal claimed that part of the world and they hated the Dutch.

The second expedition was lead by Olivier van Noort who commanded the Hoop, the Hendrik Frederik, the Mauritius, and the Eendracht. They left Amsterdam on September 15, 1598, and sailed to England to pick up Captain Melis – who had served as Drake’s chief pilot. Then they went to Africa where they encountered the Portuguese who killed Melis and others. Things got worse when the Portuguese stopped them from landing in Brazil. They lost the Eendracht, renamed the Hoop as the new Eendracht, and later lost the Hendrik Frederik.

They reached the Philippines on October 16, 1600, anchoring in the Bay of Albay. Desperate for food and supplies, van Noort (who was fluent in French) pretended to be French and was allowed to land on Capul Island. Until October 22, that is. During a skirmish off South America, they had taken captive an African slave who was loyal to Spain. The man escaped at Capul, however, so the game was up.

It did not matter. The Dutch fled and captured a Chinese junk loaded with provisions. Even better, its captain spoke Portuguese. He knew how to get to Manila, and how to navigate the busy Sino-Philippine-Indonesian-Malaysian-Indian route. He also knew the “open-times” (when it was not the deadly monsoon season).

In Manila, the Audiencia (Spanish colonial government) panicked. The capital was virtually defenseless because most of its soldiers were in Mindanao. Officially Spanish, the island was Muslim territory. They were resisting Spain not with bows, arrows, and spears; but with guns and cannons.

Fortunately, there was Don Antonio de Morga, Vice-Governor General of the Philippines. Taking command, he requisitioned two merchant galleons bound for Acapulco – the San Diego and the San Bartolomé. Loading 14 cannons aboard, he set sail looking for the Dutch, accompanied by a flotilla of smaller ships.

Finding them moored off Fortune Island, he refused to listen to their pleas for mercy and rammed the smaller Mauritius. After six hours of battle, however, the San Diego sank from a leak. Morga was the last to abandon ship. Regretfully, the Dutch got away.

Morga was hailed as a hero. His version was considered valid for centuries until Patrick Lize, a French maritime historian, became suspicious. Scouring through many records in different countries, Lize found that 24 people had survived the San Diego, including two Jesuit priests. Their version was nothing like Morga’s.

It seems the Spanish nobles treated the oncoming battle like a party. They boarded the San Diego and the San Bartolomé in their finest clothes and jewelry. They also brought along porcelain dining ware, beds, trunks, jars, and were attended by their servants and slaves.

Morga thought nothing of packing the San Diego with about 500 people in the mistaken belief that it would help him win a naval battle. The presence of Japanese, Arab, Indian, Spanish, Filipino, and African soldiers, mercenaries, servants, slaves, and nobles must have comforted him.

The merchant owner of the San Diego, Captain Alcega, asked for more ballast to be brought on board to balance the ship. Being in a hurry, Morga refused. He was in such a hurry, in fact, he ordered Alcega to set sail on December 12 without informing the San Bartolomé. Alcega then asked if the nobles could at least get rid of their bedding, dinnerware, and trunks. This request was also refused. The ship began leaning to one side but, by then, they were too far out to turn back. Nobles and commoners alike were forced to sleep on deck, since Alcega refused to dump his merchandise – he had customers waiting in Acapulco.

Outnumbered and outgunned, van Noort stayed aboard the Mauritius to buy time for the Eendracht to escape. His intel had to get back to the Netherlands.

Before dawn on December 14, the Mauritius fired the first shot at the San Diego, damaging it. The Spanish did not fire back. They could not as the ship’s deck was too crowded. Worse, it was unbalanced, so water was coming in from the gun ports. The Mauritius fired a second round, which again hit the San Diego and some of its passengers. Desperate, Morga ordered the San Diego to ram the Mauritius. It worked. Using grappling hooks, they linked up with the Dutch ship and prepared for battle… except the Dutch had retreated below decks. Opening their gun hatches, they pleaded for mercy.

Two Spanish sailors jumped aboard and grabbed the Dutch banner, expecting others to join them. None did. They returned to the San Diego to give Morga the Dutch flag, but he could not take it. The man was trembling on deck, wrapped in a kapok mattress. The chief gunner tried to take charge, but the nobles were having none of it. Orders had to come from an aristocrat like Morga. Van Noort set fire to his boat, hoping to force the Spanish into uncoupling the San Diego. That finally broke Morga out of his trance, so he ordered the lines cut.

Diego de Santiago, a priest, had had enough. He ordered people to board the Mauritius – except that chaos had broken out, by then. The Dutch, tired of waiting to be boarded, returned to their deck, put out the fire and started shooting at the San Diego.

The mooring lines were severed and the San Diego began to “sink like a stone” (according to eyewitnesses). It had taken on too much water and was too heavy. Armored men jumped overboard and sank. Unarmored nobles did the same with similar results because they refused to take off their jewelry and money pouches. Only 22 unarmored commoners survived to tell their tale.

As Morga got to tell the Spanish king his version of events first, the other versions were suppressed.

The San Diego was rediscovered by Franck Goddio (a French archeologist) in 1990. Most of its treasures are stored at the Museum of the Filipino People in Manila – an impressive display of Chinese pottery, cannons, Japanese katanas, gold and silver jewelry and coins, and so much more."

(Russell)